TSPDT placing: #10

Directed by: F.W. Murnau

Written by: Hermann Sudermann (novella), Carl Mayer (scenario), Katherine Hilliker, H.H. Caldwell (titles)

Starring: George O'Brien, Janet Gaynor, Margaret Livingston, Bodil Rosing, J. Farrell MacDonald, Ralph Sipperly

WARNING: Plot and/or ending details may follow!!!

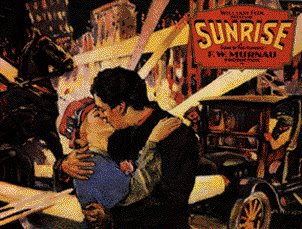

Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927) is simply one of the most breathtaking motion pictures of the silent era, and certainly one of the most effective to have originated in Hollywood. However, the film's creative talent arrived from overseas, when William Fox, founder of the Fox Films Corporation, lured prominent German director F.W. Murnau over to the United States with the promise of a greater budget and complete artistic freedom. Murnau, who had previously brought German Expressionism to its creative peak with Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens (1922) and Faust - Eine deutsche Volkssage (1926), spared no expense at his new American studio, and the result is quite possibly his most extraordinary storytelling achievement, blending reality and fantasy into a wonderfully-balanced melodramatic fable of love and redemption. Though inevitably overshadowed by the arrival of "talkies" with The Jazz Singer (1927), the film was also the first to utilize the Fox Movietone sound-on-film system, which allowed the inclusion of roughly-synchronised music, sound effects and a few garbled voices.

Just as he did in Der letzte Mann (1924), Murnau makes sparing use of intertitles, and so the film relies heavily on visuals in order to propel the story and invoke the desired mood. During his mercilessly short-lived career, the German director subscribed to two distinct film-making styles: German Expressionism, which deliberately exaggerated geometry and lighting for symbolic purposes, and the short-lived Kammerspiel ("chamber-drama") genre, most readily noticed in The Last Laugh, which bordered on neo-realistic at times, but also pioneered the moving camera in order to capture the intimacy of a character's point-of-view. Sunrise appears to have been influenced by both styles. The fable of The Man (George O'Brien) and The Wife (Janet Gaynor), its time and place purposefully vague, fittingly takes place in a plane of reality not quite aligned with our own, without straying too perceptibly into the realm of fantasy. Murnau also had mammoth sets created for the city sequences, fantastically stylised and exaggerated to re-enforce the picture's fairytale ambiance.

The characters in Sunrise are best viewed as representatives of archetypes, performing a very specific function in Murnau's moral parable. The story's primary themes are forgiveness and redemption. The Man, a misguided fool torn between two lovers, is driven to the brink of murder, but manages to stop himself at the final moment. The remainder of the film involves The Man's attempts at, not only understanding the gravity of what might have been, but also to recall his former love for his wife. I can't imagine what camera filters must have been used to transform Janet Gaynor into the supreme personification of innocence and vulnerability, but she is the most heartbreakingly-helpless figure since Lillian Gish in Broken Blossoms (1919). Even so, for the bulk of the film, the power to reconcile their estranged marriage lies solely within the hands of The Wife, whose role in the story is to recognise the remorse of her husband, and, in accordance with their sacred wedding vows, to forgive him his shameful transgressions.

The development of the moving camera was a crucial step towards the dynamic style of cinema that we now enjoy. Though the first notable use of the technique was in The Last Laugh, and Murnau is said to have used it even earlier, some of the sequences in Sunrise are simply beyond words in their gracefulness and beauty. In easily the most memorable long-take of the film, and perhaps even the decade, Karl Struss and Charles Rosher's camera sweeps behind The Man as he makes his way through the moon-lit scrub-land, before overtaking him, passing through a swathe of tree branches and arriving at The Women From the City (Margaret Livingston), who applies her make-up and waits for the married suitor whom she is about to convince to murder his wife. I first caught a split-second glimpse of this wonderful shot in Chuck Workman's montage short, Precious Images (1986), and it's a telling sign that, of all the four hundred or so movies briefly exhibited in that film, it was this one that caught my eye.

9/10

Currently my #2 film of 1927:

1) Metropolis (Fritz Lang)

2) Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (F.W. Murnau)

3) The General (Clyde Bruckman, Buster Keaton)

4) College (James W. Horne, Buster Keaton

5) The Lodger (Alfred Hitchcock) Currently my #1 film from director F.W. Murnau:

Currently my #1 film from director F.W. Murnau:

1) Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927)

2) Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens {Nosferatu} (1922)

3) Faust - Eine deutsche Volkssage {Faust} (1926)

4) Der Letzte Mann {The Last Laugh} (1924)

5) Herr Tartüff {Tartuffe} (1926)

Currently my #8 silent film:

1) Modern Times (1936, Charles Chaplin)

2) Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari. {The Cabinet Of Dr. Caligari} (1920, Robert Wiene)

3) Metropolis (1927, Fritz Lang)

4) Frau im Mond {Woman in the Moon} (1929, Fritz Lang)

5) Körkarlen {The Phantom Chariot} (1921, Victor Sjöström)

6) City Lights (1931, Charles Chaplin)

7) Sherlock Jr. (1924, Buster Keaton)

8) Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927, F.W. Murnau)

9) Bronenosets Potyomkin {The Battleship Potemkin} (1925, Sergei M. Eisenstein)

10) Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens {Nosferatu} (1922, F.W. Murnau)

1st Academy Awards, 1929:

* Best Picture, Unique and Artistic Production (win)

* Best Cinematography - Charles Rosher, Karl Struss (win)

* Best Actress in a Leading Role - Janet Gaynor (also for Seventh Heaven (1927) and Street Angel (1928)) (win)

* Best Art Direction - Rochus Gliese (nomination)

National Film Preservation Board, USA:

* Selected for National Film Registry, 1989 Extracts from reviews of other Murnau pictures:

Extracts from reviews of other Murnau pictures:

"To fans of early horror, director F.W. Murnau is best known for Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens, his chilling 1922 vampire film, inspired by Bram Stoker's famous novel. However, his equally impressive Faust (1926) is often overlooked, despite some remarkable visuals, solid acting, a truly sinister villain, and an epic tale of love, loss and evil... Relying very heavily on visuals, 'Faust' contains some truly stunning on screen imagery, most memorably the inspired shot of Mephisto towering ominously over a town, preparing to sow the seeds of the Black Death. A combination of clever optical trickery and vibrant costumes and sets makes the film an absolute delight to watch, with Murnau employing every known element – fire, wind, smoke, lightning – to help produce the film's dark tone. Double exposure is used extremely effectively, being an integral component in many of the visual effects shots."

"Frequent collaborator Emil Jannings is undoubtedly the star of The Last Laugh (1924), occupying almost the entire screen time, and playing the character about whom the story revolves. Performing with a passion that transcends the technical boundaries of the silent film, Jannings gives a truly heart-breaking performance that is worth the price of admission alone... I found myself likening the style to that of the Italin neo-realism movement, if only for showing an average, not-particularly-important man overwhelmed by the cruelty of upper-class society. However, several scenes diverge from this mould, most specifically a dizzying, wondrous dream sequence, and a tacked-on optimistic ending imposed by the commercially-insecure studio. Though it was not the first film to exploit a moving camera, I've rarely seen a silent film making better use of the technique."

"Herr Tartüff / Tartuffe (1925) was apparently forced upon Murnau by contractual obligations with Universum Film (UFA), and you suspect that perhaps his heart wasn't quite in it, but the end result nonetheless remains essential viewing, as are all the director's films... The tale of Tartuffe himself is worth watching for its technical accomplishments, even if the story itself seems somewhat generic and uninteresting. Most astounding is Murnau's exceptional use of lighting {assisted, of course, by cinematographer Karl Freund}, and, in many cases, entire rooms are seemingly being illuminated only by candlelight... Jannings predictably gives the finest performance, playing the unsavoury title character with a mixture of sly arrogance and lustful repugnance; nevertheless, the role falls far short of the silent actor's greatest performances..."

Peter Sellers is often held to be among cinema's most accomplished comedians, and I can see no reason why this should not be the case. He was an extraordinary chameleon when the role called for it, and no actor ever milked so many laughs from his manipulation of cultural stereotypes, whether that be his fascist German from Dr. Strangelove…, his bumbling Frenchman from The Pink Panther, his vocabulary-challenged Chinese detective from Murder by Death (1976) or his good-natured Indian from this film. Of course, it takes a few moments for you to accept such a well-known actor as playing an Indian, but, by the film's end, it doesn't seem unusual in the slightest. Sellers plays Hrundi V. Bakshi as an affable and friendly outsider, completely out-of-his-depth at such an upper-class get-together. Despite his occasionally tendency to be rather clumsy, he eventually earns the respect of the other party-goers, especially beautiful actress Michele Monet (Claudine Longet), through his kindness and indomitable sense of fun.

Peter Sellers is often held to be among cinema's most accomplished comedians, and I can see no reason why this should not be the case. He was an extraordinary chameleon when the role called for it, and no actor ever milked so many laughs from his manipulation of cultural stereotypes, whether that be his fascist German from Dr. Strangelove…, his bumbling Frenchman from The Pink Panther, his vocabulary-challenged Chinese detective from Murder by Death (1976) or his good-natured Indian from this film. Of course, it takes a few moments for you to accept such a well-known actor as playing an Indian, but, by the film's end, it doesn't seem unusual in the slightest. Sellers plays Hrundi V. Bakshi as an affable and friendly outsider, completely out-of-his-depth at such an upper-class get-together. Despite his occasionally tendency to be rather clumsy, he eventually earns the respect of the other party-goers, especially beautiful actress Michele Monet (Claudine Longet), through his kindness and indomitable sense of fun. The Party was largely improvised from a rudimentary 56-60 page screenplay, and it really does show. There is nothing exceptional about the dialogue, and, though Bakshi gets one or two memorable catch-phrases ("Birdie Num Num!"), the bulk of the humour is purely visual. There was always going to be a risk in extending a single party throughout a 99-minute running-time, and the end result is rather interesting. Between gags, particularly during the dinner sequence, there is a curious sense of vacuousness, and Edwards indulges in an extended period of idleness that no comedy director today would ever be bold enough to leave intact. In one way, this approach is somewhat reassuring; the director is obviously completely comfortable with what he is doing. On the other hand, you wonder if the story is merely stalling itself, in order to consume enough celluloid to make a respectable feature-length. In any case, despite my adverse expectations, The Party turned out to be an adequately funny and even touching comedy, in no small part due to the magnificent talents of its leading man…whatever nationality he might be.

The Party was largely improvised from a rudimentary 56-60 page screenplay, and it really does show. There is nothing exceptional about the dialogue, and, though Bakshi gets one or two memorable catch-phrases ("Birdie Num Num!"), the bulk of the humour is purely visual. There was always going to be a risk in extending a single party throughout a 99-minute running-time, and the end result is rather interesting. Between gags, particularly during the dinner sequence, there is a curious sense of vacuousness, and Edwards indulges in an extended period of idleness that no comedy director today would ever be bold enough to leave intact. In one way, this approach is somewhat reassuring; the director is obviously completely comfortable with what he is doing. On the other hand, you wonder if the story is merely stalling itself, in order to consume enough celluloid to make a respectable feature-length. In any case, despite my adverse expectations, The Party turned out to be an adequately funny and even touching comedy, in no small part due to the magnificent talents of its leading man…whatever nationality he might be. Animation, perhaps even more than its live-action counterpart, has the incredible ability to draw a viewer entirely into its world, to construct a completely new dimension of reality. Everything you see onscreen is the product of the animators' imaginations, every subtle stroke purposefully conceived and painstakingly brought into existence.

Animation, perhaps even more than its live-action counterpart, has the incredible ability to draw a viewer entirely into its world, to construct a completely new dimension of reality. Everything you see onscreen is the product of the animators' imaginations, every subtle stroke purposefully conceived and painstakingly brought into existence. 8)

8)  6)

6)  4)

4)  2)

2)  Ah, Casablanca. What other film can evoke such powerful feelings of nostalgia, can exemplify so completely the golden period of Hollywood film-making? The year was 1942, and the world found itself in the midst of the bloodiest conflict in modern history. Unlike anything our generation could possibly imagine, citizens were faced with an incredible uncertainty about their future. The Nazis marched across Europe, an astonishing, seemingly-unstoppable enemy, and the United States watched with bated breath from across the Atlantic. Most Hollywood productions responded to such ambiguity with fully-fledged, unabashed patriotism, and war-time filmmakers became obsessed with validating audiences' beliefs that the Allied forces would inevitably win out against Germany, and, indeed, many often concluded their pictures with unnecessary epilogues in which we've apparently already won. Such propaganda, while no doubt ensuring commercial success from war-weary cinema-goers, has regularly tarnished and outdated even the most otherwise-impressive contemporary WWII pictures, as the directors' willingness to simulate a happy ending strikes distinctly false from an era in which the overwhelming atmosphere was that of uncertainty and insecurity {see Billy Wilder's Five Graves to Cairo (1943)}.

Ah, Casablanca. What other film can evoke such powerful feelings of nostalgia, can exemplify so completely the golden period of Hollywood film-making? The year was 1942, and the world found itself in the midst of the bloodiest conflict in modern history. Unlike anything our generation could possibly imagine, citizens were faced with an incredible uncertainty about their future. The Nazis marched across Europe, an astonishing, seemingly-unstoppable enemy, and the United States watched with bated breath from across the Atlantic. Most Hollywood productions responded to such ambiguity with fully-fledged, unabashed patriotism, and war-time filmmakers became obsessed with validating audiences' beliefs that the Allied forces would inevitably win out against Germany, and, indeed, many often concluded their pictures with unnecessary epilogues in which we've apparently already won. Such propaganda, while no doubt ensuring commercial success from war-weary cinema-goers, has regularly tarnished and outdated even the most otherwise-impressive contemporary WWII pictures, as the directors' willingness to simulate a happy ending strikes distinctly false from an era in which the overwhelming atmosphere was that of uncertainty and insecurity {see Billy Wilder's Five Graves to Cairo (1943)}. When Casablanca was first conceived, the filmmakers apparently had little idea they were about to produce one of cinema's best-loved pictures. A prime example of the studio-bound exotica that was popular at the time, and obviously a war-time off-shoot of Howard Hawks' Colombian aviation adventure

When Casablanca was first conceived, the filmmakers apparently had little idea they were about to produce one of cinema's best-loved pictures. A prime example of the studio-bound exotica that was popular at the time, and obviously a war-time off-shoot of Howard Hawks' Colombian aviation adventure  Perhaps another possible explanation for the film's unlikely legacy lies with the distinguished cast, borrowed from all over Europe. Humphrey Bogart, Dooley Wilson and Joy Page were the sole American "imports," and assorted supporting talents were plundered from the United Kingdom (Claude Rains, Sydney Greenstreet), Sweden (Ingrid Bergman), Austria (Paul Henreid), Hungary (Peter Lorre) and even Germany (Conrad Veidt, who fled the Nazi regime in 1933 after marrying a Jewish woman). Bogart, who had been typecast throughout the 1930s as a lowlife gangster, had been given the opportunity to show some humanity in Raoul Walsh' film noir High Sierra (1941), but it was Casablanca that proved his first genuinely romantic role, and, with several notable exceptions, the remainder of his acting career would comprise of similarly-noble yet flawed heroes. Bergman, despite having a rather passive role, was never more enchanting than as Ilsa Lund, and, photographed with a softening gauze filter and catch lights, positively sparkles with gentle compassion and sadness.

Perhaps another possible explanation for the film's unlikely legacy lies with the distinguished cast, borrowed from all over Europe. Humphrey Bogart, Dooley Wilson and Joy Page were the sole American "imports," and assorted supporting talents were plundered from the United Kingdom (Claude Rains, Sydney Greenstreet), Sweden (Ingrid Bergman), Austria (Paul Henreid), Hungary (Peter Lorre) and even Germany (Conrad Veidt, who fled the Nazi regime in 1933 after marrying a Jewish woman). Bogart, who had been typecast throughout the 1930s as a lowlife gangster, had been given the opportunity to show some humanity in Raoul Walsh' film noir High Sierra (1941), but it was Casablanca that proved his first genuinely romantic role, and, with several notable exceptions, the remainder of his acting career would comprise of similarly-noble yet flawed heroes. Bergman, despite having a rather passive role, was never more enchanting than as Ilsa Lund, and, photographed with a softening gauze filter and catch lights, positively sparkles with gentle compassion and sadness.

Aside from Allen and Keaton, numerous smaller roles provide a crucial framework for the overall structure of the film. Tony Roberts is Rob, Singer's old friend and confidant. Paul Simon (of Simon and Garfunkel) plays a record producer who takes a keen interest in both Annie and her singing. Shelley Duvall is a reporter for 'The Rolling Stone' magazine, and a one-time girlfriend of Singer. There are also tiny early roles for Christopher Walken (as Annie's somewhat disturbed brother), Jeff Goldblum (who speaks one memorable line at a party – "Hello? I forgot my mantra") and Sigourney Weaver (who can be briefly glimpsed as Singer's date outside a theatre). Two slightly more unusual cameos come from Truman Capote (as a Truman Capote-lookalike, no less) and scholar Marshall McLuhan (whom Singer suddenly procures from behind a movie poster to declare to a talkative film-goer that "you know nothing of my work!").

Aside from Allen and Keaton, numerous smaller roles provide a crucial framework for the overall structure of the film. Tony Roberts is Rob, Singer's old friend and confidant. Paul Simon (of Simon and Garfunkel) plays a record producer who takes a keen interest in both Annie and her singing. Shelley Duvall is a reporter for 'The Rolling Stone' magazine, and a one-time girlfriend of Singer. There are also tiny early roles for Christopher Walken (as Annie's somewhat disturbed brother), Jeff Goldblum (who speaks one memorable line at a party – "Hello? I forgot my mantra") and Sigourney Weaver (who can be briefly glimpsed as Singer's date outside a theatre). Two slightly more unusual cameos come from Truman Capote (as a Truman Capote-lookalike, no less) and scholar Marshall McLuhan (whom Singer suddenly procures from behind a movie poster to declare to a talkative film-goer that "you know nothing of my work!"). Unlike some gangster pictures, which tend to take a few minutes to swing into gear, White Heat opens with a daring railway robbery, in which Jarrett and his gang murder four innocent men and flee with thousands of dollars in cash. In order to escape the gas chamber, the master-criminal surrenders to the authorities and claims responsibility for a minor hotel heist, receiving 1-3 years imprisonment but eluding suspicions that he played a role in the bloody train robbery. The detectives in charge, however, remain unconvinced, and dedicated undercover agent Hank Fallon (Edmond O'Brien) is sent to the prison to gain Jarrett's trust and acquire evidence of his involvement in the crime. Meanwhile, opportunistic femme fatale, Verna (Virginia Mayo), plays a deadly game with treacherous associate Big Ed (Steve Cochran), while Jarrett's predatory mother (Margaret Wycherly) seethes ominously in the shadows. When Jarrett and a gang of lackeys stage an exciting jail-break, Fallon attempts to alert the authorities to his latest movements – but this felon isn't going to take failure lying down.

Unlike some gangster pictures, which tend to take a few minutes to swing into gear, White Heat opens with a daring railway robbery, in which Jarrett and his gang murder four innocent men and flee with thousands of dollars in cash. In order to escape the gas chamber, the master-criminal surrenders to the authorities and claims responsibility for a minor hotel heist, receiving 1-3 years imprisonment but eluding suspicions that he played a role in the bloody train robbery. The detectives in charge, however, remain unconvinced, and dedicated undercover agent Hank Fallon (Edmond O'Brien) is sent to the prison to gain Jarrett's trust and acquire evidence of his involvement in the crime. Meanwhile, opportunistic femme fatale, Verna (Virginia Mayo), plays a deadly game with treacherous associate Big Ed (Steve Cochran), while Jarrett's predatory mother (Margaret Wycherly) seethes ominously in the shadows. When Jarrett and a gang of lackeys stage an exciting jail-break, Fallon attempts to alert the authorities to his latest movements – but this felon isn't going to take failure lying down. White Heat played an important role in the development of the heist picture sub-genre, and, like Walsh's High Sierra (1941) years earlier, paved the way for the classic and influential narrative formula to be found in John Huston's

White Heat played an important role in the development of the heist picture sub-genre, and, like Walsh's High Sierra (1941) years earlier, paved the way for the classic and influential narrative formula to be found in John Huston's  A perfect example of the film's style of satire can be found early on, after veteran news anchorman Howard Beale (Peter Finch) learns that he is to be fired in two weeks' time, on account of poor ratings. The following evening, Beale calmly announces to millions of Americans his intentions to commit suicide on the air in a week's time. The show's technicians idly go about their duties, oblivious to what their star has just proclaimed, before one employee tentatively ventures, "uh, did you hear what Howard just said?" The network, in their ongoing quest for high ratings, was so blindly obsessed with perfecting all their technical aspects that the mental-derangement of their leading anchorman went almost completely unnoticed. At first, there is an attempt to yank Beale from the air, but one forward-thinking producer, Diana Christensen (Faye Dunaway), proposes that the network could double their current ratings by keeping him in the spotlight.

A perfect example of the film's style of satire can be found early on, after veteran news anchorman Howard Beale (Peter Finch) learns that he is to be fired in two weeks' time, on account of poor ratings. The following evening, Beale calmly announces to millions of Americans his intentions to commit suicide on the air in a week's time. The show's technicians idly go about their duties, oblivious to what their star has just proclaimed, before one employee tentatively ventures, "uh, did you hear what Howard just said?" The network, in their ongoing quest for high ratings, was so blindly obsessed with perfecting all their technical aspects that the mental-derangement of their leading anchorman went almost completely unnoticed. At first, there is an attempt to yank Beale from the air, but one forward-thinking producer, Diana Christensen (Faye Dunaway), proposes that the network could double their current ratings by keeping him in the spotlight.  Peter Finch, who was awarded a posthumous Best Actor Oscar for his performance, is simply explosive as the unhinged anchorman whose volatile outbursts of derangement are celebrated by a society which, in a better world, should be trying to help him. Beale's memorable catch-cry – "I'm as mad as hell, and I'm not going to take this anymore!" – symbolises his revulsion towards the crumbling values of today's society, and, as fanatical as he might be, most of his raves are worryingly close to the truth. William Holden is also excellent as Max Schumacher, Beale's long-time colleague, who resents the networks' treatment of his friend, but does little to interfere. Schumacher's adulterous relationship with the seductive but soulless Diana (Dunaway) consciously follows the conventional path of a television soap opera, ending with the realisation that his affair with the ratings-obsessed mistress is sapping him of any real emotion or humanity; in Schumacher's own words, "after living with you for six months, I'm turning into one of your scripts." Television corrupts life.

Peter Finch, who was awarded a posthumous Best Actor Oscar for his performance, is simply explosive as the unhinged anchorman whose volatile outbursts of derangement are celebrated by a society which, in a better world, should be trying to help him. Beale's memorable catch-cry – "I'm as mad as hell, and I'm not going to take this anymore!" – symbolises his revulsion towards the crumbling values of today's society, and, as fanatical as he might be, most of his raves are worryingly close to the truth. William Holden is also excellent as Max Schumacher, Beale's long-time colleague, who resents the networks' treatment of his friend, but does little to interfere. Schumacher's adulterous relationship with the seductive but soulless Diana (Dunaway) consciously follows the conventional path of a television soap opera, ending with the realisation that his affair with the ratings-obsessed mistress is sapping him of any real emotion or humanity; in Schumacher's own words, "after living with you for six months, I'm turning into one of your scripts." Television corrupts life.

_poster.jpg)