TSPDT placing: #797

Directed by: Alan J. Pakula

Written by: Andy Lewis, David P. Lewis

Starring: Jane Fonda, Donald Sutherland, Roy Scheider, Charles Cioffi, Dorothy Tristan

For the most part, the advent of sound was utilised simply to accompany the on screen action. In Klute (1971), director Alan J. Pakula does something very interesting: he uses audio to layer one scene on top of another. Call-girl Bree Daniels (Jane Fonda), held at the whim of a desperate sexual deviant, is forced to hear the tape recording of a murder. The camera never leaves Bree's face, but the viewer barely sees her. Instead, the mind conjures up an entire scene that was never filmed, the sickening final moments of a drug-addled prostitute at the hands of a disturbed man. A less-assured director might have used video footage, or even a flashback. Pakula understood that the audience would provide its own flashback, and his merging of disparate visual and audio streams allows him to tell two stories at once. In this respect, I wouldn't be surprised if the film was the partial inspiration (along with Antonioni's Blow Up (1966), of course) for Coppola's The Conversation (1974). Though the film takes its title from Donald Sutherland's small-town detective John Klute, the character himself remains oddly detached throughout. Instead, Pakula is most concerned with Fonda's reluctant call-girl, an aspiring actress who keeps returning to prostitution because it involves an "acting performance" during which she always feels in control. Fonda brings an acute warmth and vulnerability to a film that is, by design, rather cold and detached. Pakula deliberately distances the viewer from the story, placing his audience – not in the room where the action is taking place – but on the opposite end of a recording device. His accusation that the viewer is himself engaging in voyeurism runs alongside such films as Powell's Peeping Tom (1960), Antonioni's Blow Up and many works of Hitchcock. It is Fonda's performance that gives the film its core, more so than the mystery itself, the solution of which is offered early on. However, the extra details we glean from Bree's regular visits to a therapist could easily have been peppered more subtly throughout the film.

Though the film takes its title from Donald Sutherland's small-town detective John Klute, the character himself remains oddly detached throughout. Instead, Pakula is most concerned with Fonda's reluctant call-girl, an aspiring actress who keeps returning to prostitution because it involves an "acting performance" during which she always feels in control. Fonda brings an acute warmth and vulnerability to a film that is, by design, rather cold and detached. Pakula deliberately distances the viewer from the story, placing his audience – not in the room where the action is taking place – but on the opposite end of a recording device. His accusation that the viewer is himself engaging in voyeurism runs alongside such films as Powell's Peeping Tom (1960), Antonioni's Blow Up and many works of Hitchcock. It is Fonda's performance that gives the film its core, more so than the mystery itself, the solution of which is offered early on. However, the extra details we glean from Bree's regular visits to a therapist could easily have been peppered more subtly throughout the film.

8/10

Currently my #5 film of 1971:

1) A Clockwork Orange (Stanley Kubrick)

2) Straw Dogs (Sam Peckinpah)

3) Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory (Mel Stuart)

4) The French Connection (William Friedkin)

5) Klute (Alan J. Pakula)

6) Get Carter (Mike Hodges)

7) Bananas (Woody Allen)

8) The Stalls of Barchester (Lawrence Gordon Clark) (TV)

Saturday, December 26, 2009

Target #284: Klute (1971, Alan J. Pakula)

Friday, September 18, 2009

Target #281: JFK (1991, Oliver Stone)

TSPDT placing: #492

Directed by: Oliver Stone

Written by: Jim Garrison (book), Jim Marrs (book), Oliver Stone (screenplay), Zachary Sklar (screenplay)

Starring: Kevin Costner, Jack Lemmon, Gary Oldman, Sissy Spacek, Michael Rooker, Joe Pesci, Walter Matthau, Tommy Lee Jones, John Candy, Kevin Bacon, Donald Sutherland

Oliver Stone's wildly-speculative conspiracy theory epic JFK (1991) opens with a montage of archival footage depicting the presidency of John F. Kennedy, 35th President of the United States, up until 12:30PM on Friday, November 22, 1963, in Dallas, Texas. However, even before this historical prologue has come to an end, Stone has already introduced his own dramatisation – a beaten prostitute, dumped on the side of a road, pleads that Kennedy's life is in danger. Her agonised cries play over familiar documentary footage of the Presidential motorcade. Already, Stone is defiantly blending fact and fiction, speculation and dramatisation. On its initial release, the film stirred enormous controversy due to its flagrant disregard for historical fact, but that's not what JFK is all about. Oliver Stone may (or may not) genuinely believe all of Jim Garrison's conspiracy theories – which implicate everybody up to former President Lyndon B. Johnson – but his film nevertheless offers a tantalising "what if?" scenario, an unsettling portrait of the fallibility of "history" itself.

Having undertaken some light research, I don't feel that Garrison's claims hold much water. However, that doesn't detract from the film's brilliance. Crucial is Stone's more generalised vibe of government mistrust, the acknowledgement that political institutions are at least conceptually capable of such a wide-ranging operation to hoodwink the American public. JFK also paints a gripping picture of its protagonist, torn between its admiration for a man willing to contest the sacred cow of US government, and its pity for one so hopelessly obsessed with conspiracy that it consumes his life, family and livelihood. Kevin Costner plays Garrison as righteous and stubbornly idealistic, not dissimilar to his Eliot Ness in De Palma's The Untouchables (1987). The only difference is that Garrison is chasing a criminal far more transparent than Al Capone – indeed, a criminal who may not exist at all. Costner is supported by an exceedingly impressive supporting cast: Jack Lemmon, Walter Matthau, Kevin Bacon, Donald Sutherland, Joe Pesci, Michael Rooker, Tommy Lee Jones, Gary Oldman and John Candy.

Having undertaken some light research, I don't feel that Garrison's claims hold much water. However, that doesn't detract from the film's brilliance. Crucial is Stone's more generalised vibe of government mistrust, the acknowledgement that political institutions are at least conceptually capable of such a wide-ranging operation to hoodwink the American public. JFK also paints a gripping picture of its protagonist, torn between its admiration for a man willing to contest the sacred cow of US government, and its pity for one so hopelessly obsessed with conspiracy that it consumes his life, family and livelihood. Kevin Costner plays Garrison as righteous and stubbornly idealistic, not dissimilar to his Eliot Ness in De Palma's The Untouchables (1987). The only difference is that Garrison is chasing a criminal far more transparent than Al Capone – indeed, a criminal who may not exist at all. Costner is supported by an exceedingly impressive supporting cast: Jack Lemmon, Walter Matthau, Kevin Bacon, Donald Sutherland, Joe Pesci, Michael Rooker, Tommy Lee Jones, Gary Oldman and John Candy. With the Director's Cut clocking in at 206 minutes, JFK is an epic piece of work. However, the film is so dazzlingly well-constructed that watching it becomes less of a choice than a compulsion. Stone frenziedly throws together seemingly-unrelated puzzle-pieces, systematically peeling back layer after layer of conspiracy until all that remains is what Jim Garrison believes to be the naked truth. Beneath the sordid details, Stone speculates on the nature of history itself. Archive footage blends seamlessly with dramatisation – but what is recorded history but a re-enactment submitted by the winners? Not even the witnesses to Kennedy's assassination, clouded by subjective perception, can know for sure what exactly took place on that dark day in Dallas. Perhaps Zapruder's 486 frames of grainy hand-held footage (combined with that of Nix and Muchmore) represents the only objective record of the event – but Antonioni's Blowup (1966) argued that even photographic documentation is unreliable through the inherent bias of the viewer. In short, nobody knows what really happened that day. JFK is Oliver Stone creating his own history – or merely correcting it.

With the Director's Cut clocking in at 206 minutes, JFK is an epic piece of work. However, the film is so dazzlingly well-constructed that watching it becomes less of a choice than a compulsion. Stone frenziedly throws together seemingly-unrelated puzzle-pieces, systematically peeling back layer after layer of conspiracy until all that remains is what Jim Garrison believes to be the naked truth. Beneath the sordid details, Stone speculates on the nature of history itself. Archive footage blends seamlessly with dramatisation – but what is recorded history but a re-enactment submitted by the winners? Not even the witnesses to Kennedy's assassination, clouded by subjective perception, can know for sure what exactly took place on that dark day in Dallas. Perhaps Zapruder's 486 frames of grainy hand-held footage (combined with that of Nix and Muchmore) represents the only objective record of the event – but Antonioni's Blowup (1966) argued that even photographic documentation is unreliable through the inherent bias of the viewer. In short, nobody knows what really happened that day. JFK is Oliver Stone creating his own history – or merely correcting it.9/10

Currently my #3 film of 1991:

1) The Silence of the Lambs (Jonathan Demme)

2) Terminator 2: Judgment Day (James Cameron)

3) JFK (Oliver Stone)

4) Hearts Of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse (Fax Bahr, George Hickenlooper, Eleanor Coppola)

5) Barton Fink (Joel Coen, Ethan Coen)

Tuesday, July 21, 2009

Repeat Viewing: North by Northwest (1959, Alfred Hitchcock)

TSPDT placing: #49

Ernest Lehman's screenplay outwardly appears to be little but a selection of spectacular set-pieces strung together by Hitchcock's trademark "wrong man" motif, but it nonetheless amply supports its running-time (among the director's longest). Cary Grant's charming banter with double-agent Eva Marie Saint is tinged with sly sexual innuendo, and only Hitchcock could have ended a film with the hero's train entering the leading ladies'…. well, you get the picture. James Mason brings a dignified vulnerability to the role of Commie spy Phillip Vandamm, but Hitchcock seems only marginally interested in the character, and, indeed, his ultimate fate is completely skipped over (instead, Martin Landau's vicious henchman is given an arch-villain's death). Hitchcock's climax atop a studio reconstruction of Mount Rushmore is only effective thanks to Bernard Hermann's momentous score, but other sequences reek of the director's astonishing aptitude for suspense. The breathless crop-duster ambush is worthy of every accolade that has been bestowed upon it, and Grant's comedic talents shine during both a drunken roadside escape and an impromptu auction-house heckle.

Ernest Lehman's screenplay outwardly appears to be little but a selection of spectacular set-pieces strung together by Hitchcock's trademark "wrong man" motif, but it nonetheless amply supports its running-time (among the director's longest). Cary Grant's charming banter with double-agent Eva Marie Saint is tinged with sly sexual innuendo, and only Hitchcock could have ended a film with the hero's train entering the leading ladies'…. well, you get the picture. James Mason brings a dignified vulnerability to the role of Commie spy Phillip Vandamm, but Hitchcock seems only marginally interested in the character, and, indeed, his ultimate fate is completely skipped over (instead, Martin Landau's vicious henchman is given an arch-villain's death). Hitchcock's climax atop a studio reconstruction of Mount Rushmore is only effective thanks to Bernard Hermann's momentous score, but other sequences reek of the director's astonishing aptitude for suspense. The breathless crop-duster ambush is worthy of every accolade that has been bestowed upon it, and Grant's comedic talents shine during both a drunken roadside escape and an impromptu auction-house heckle. That the audience learns of George Kaplan's fictitiousness long before Thornhill ever does may admittedly weaken the suspense, but Hitchcock's motives are instead to recruit the audience into his own position, as director, of omnipotent power. Beneath its surface, North by Northwest appears to be a subtle swing at Cold War politics, and particularly the power wielded by the FBI and government committees like the HUAC. As Thornhill fights to unravel himself from a tangled web of deception and espionage, Hitchcock unexpectedly crosses to a panel of FBI agents, headed by Leo G. Carroll, who bicker indifferently over the mess into which they've got this oblivious pawn. These government employees are happy to sit listlessly by as citizens place their lives on the line, their quarrels bizarrely resembling the conversations of the gods in Jason and the Argonauts (1963). Indeed, like deities, the FBI men wield the power to invent (Kaplan), destroy, or even resurrect (Thornhill) human beings, and intercede sporadically in a suitably Deus Ex Machina-like fashion.

That the audience learns of George Kaplan's fictitiousness long before Thornhill ever does may admittedly weaken the suspense, but Hitchcock's motives are instead to recruit the audience into his own position, as director, of omnipotent power. Beneath its surface, North by Northwest appears to be a subtle swing at Cold War politics, and particularly the power wielded by the FBI and government committees like the HUAC. As Thornhill fights to unravel himself from a tangled web of deception and espionage, Hitchcock unexpectedly crosses to a panel of FBI agents, headed by Leo G. Carroll, who bicker indifferently over the mess into which they've got this oblivious pawn. These government employees are happy to sit listlessly by as citizens place their lives on the line, their quarrels bizarrely resembling the conversations of the gods in Jason and the Argonauts (1963). Indeed, like deities, the FBI men wield the power to invent (Kaplan), destroy, or even resurrect (Thornhill) human beings, and intercede sporadically in a suitably Deus Ex Machina-like fashion.2) Room at the Top (Jack Clayton)

3) North by Northwest (Alfred Hitchcock)

4) Some Like It Hot (Billy Wilder)

5) Our Man in Havana (Carol Reed)

6) On the Beach (Stanley Kramer)

7) Le Quatre cents coups {The 400 Blows} (François Truffaut)

8) Pickpocket (Robert Bresson)

9) Ben-Hur (William Wyler)

10) The Tingler (William Castle)

Thursday, January 1, 2009

Target #255: Le Salaire de la peur / The Wages of Fear (1953, Henri-Georges Clouzot)

TSPDT placing: #206

Directed by: Henri-Georges Clouzot

Written by: Georges Arnaud (novel), Henri-Georges Clouzot (writer), Jérôme Géronimi (writer)

Starring: Yves Montand, Charles Vanel, Folco Lulli, Peter van Eyck, Véra Clouzot, William Tubbs, Darío Moreno, Jo Dest

WARNING: Plot and/or ending details may follow!!!

For a brief period during the 1950s, French director Henri-Georges Clouzot captured the mantle of "The Master of Suspense" from Alfred Hitchcock, owing mostly to his two most recognised thrillers, The Wages of Fear (1953) and Les Diaboliques (1955). It's a difficult title to live up to, but Clouzot knows precisely what he's doing, even if he seems to lack Hitchcock's distinctive sense of showmanship. What I've always loved about cinema is its ability to manipulate reality, to elicit genuine emotions from situations that, in real life, would seem mundane, or even ridiculous. An example I've used before, I believe, is Tarkovsky's Stalker (1979), in which a peaceful and benign forest is inexplicably transformed into an environment of intense mystery and foreboding. Now consider The Wages of Fear, when actor Peter van Eyck funnels what is probably water into a drilled hole in the rock. There's zero suspense in this simple act of pouring. However, taken within the context of the story, this water suddenly becomes nitroglycerine, and I got sore fingers from gripping the chair so tightly.

8/10

Currently my #5 film of 1953:

1) From Here To Eternity (Fred Zinnemann)

2) Stalag 17 (Billy Wilder)

3) I Confess (Alfred Hitchcock)

4) The Titfield Thunderbolt (Charles Crichton)

5) Le salaire de la peur {The Wages of Fear} (Henri-Georges Clouzot)

6) Pickup on South Street (Samuel Fuller)

7) Roman Holiday (William Wyler)

8) The War Of The Worlds (Byron Haskin)

Monday, December 29, 2008

Target #254: Pickup on South Street (1953, Samuel Fuller)

TSPDT placing: #737

When just-out-of-prison pickpocket Skip McCoy (Richard Widmark) snags the purse of a woman on the subway (Jean Peters), he pockets more than he'd originally bargained for. The woman, Candy, and her cowardly ex-boyfriend Joey (Richard Kiley) had been smuggling top-secret information to the Communists, and McKoy has unexpectedly retrieved an important roll of micro-film. Will he turn in the MacGuffin to the proper authorities, or sell it to the highest bidder? If Pickup on South Street has a flaw, it's that the story seems designed solely to bolster an anti-Communist agenda, reeking of propaganda like nothing since WWII {Dwight Taylor, who supplied the story, also notably wrote The Thin Man Goes Home (1944), the only propagandistic movie of the series}. For no apparent reason, every identifiable character – even the smugly self-serving Skip McCoy – eventually becomes a self-sacrificing patriot, the transformation predictable from the outset. In traditional film noir, the unapologetic criminal always gets his comeuppance, the rational punishment for his sins, but apparently not when they've served their country; patriotism wipes the slate clean.

When just-out-of-prison pickpocket Skip McCoy (Richard Widmark) snags the purse of a woman on the subway (Jean Peters), he pockets more than he'd originally bargained for. The woman, Candy, and her cowardly ex-boyfriend Joey (Richard Kiley) had been smuggling top-secret information to the Communists, and McKoy has unexpectedly retrieved an important roll of micro-film. Will he turn in the MacGuffin to the proper authorities, or sell it to the highest bidder? If Pickup on South Street has a flaw, it's that the story seems designed solely to bolster an anti-Communist agenda, reeking of propaganda like nothing since WWII {Dwight Taylor, who supplied the story, also notably wrote The Thin Man Goes Home (1944), the only propagandistic movie of the series}. For no apparent reason, every identifiable character – even the smugly self-serving Skip McCoy – eventually becomes a self-sacrificing patriot, the transformation predictable from the outset. In traditional film noir, the unapologetic criminal always gets his comeuppance, the rational punishment for his sins, but apparently not when they've served their country; patriotism wipes the slate clean. Richard Widmark, an actor who I'm really beginning to like, plays the haughty pickpocket with composure, though always with that hint of ill-ease that suggests he's biting off more than he can chew. The opening scene on the train is the film's finest, as McCoy breathlessly fishes around in his victim's hand bag, recalling Bresson's Pickpocket (1959). Thelma Ritter is terrific as a tired street-woman who'll peddle information to anybody willing to pay for it (though, of course, she draws the line at Commies). Jean Peters is well-cast as the trashy dame passing information to the other side, playing the role almost completely devoid of glamour; Fuller reportedly cast the actress on the observation that she had the slightly bow-legged strut of a prostitute. Nevertheless, Peters must suffer a contrived love affair with Widmark that really brings down the film's attempts at realism. Fascinatingly, upon its release, Pickup on South Street was promptly condemned as Communist propaganda by the FBI, and the Communist Party condemned it for being the exact opposite. Go figure.

Richard Widmark, an actor who I'm really beginning to like, plays the haughty pickpocket with composure, though always with that hint of ill-ease that suggests he's biting off more than he can chew. The opening scene on the train is the film's finest, as McCoy breathlessly fishes around in his victim's hand bag, recalling Bresson's Pickpocket (1959). Thelma Ritter is terrific as a tired street-woman who'll peddle information to anybody willing to pay for it (though, of course, she draws the line at Commies). Jean Peters is well-cast as the trashy dame passing information to the other side, playing the role almost completely devoid of glamour; Fuller reportedly cast the actress on the observation that she had the slightly bow-legged strut of a prostitute. Nevertheless, Peters must suffer a contrived love affair with Widmark that really brings down the film's attempts at realism. Fascinatingly, upon its release, Pickup on South Street was promptly condemned as Communist propaganda by the FBI, and the Communist Party condemned it for being the exact opposite. Go figure.2) Stalag 17 (Billy Wilder)

3) I Confess (Alfred Hitchcock)

4) The Titfield Thunderbolt (Charles Crichton)

5) Pickup on South Street (Samuel Fuller)

6) Roman Holiday (William Wyler)

7) The War Of The Worlds (Byron Haskin)

Friday, December 26, 2008

Target #252: Heat (1995, Michael Mann)

TSPDT placing: #381

Directed by: Michael Mann

Written by: Michael Mann

Starring: Al Pacino, Robert De Niro, Val Kilmer, Jon Voight, Tom Sizemore, Diane Venora, Amy Brenneman, Ashley Judd, Mykelti Williamson, Dennis Haysbert, William Fichtner, Natalie Portman

WARNING: Plot and/or ending details may follow!!! [Paragraph 2 only]

Like him or not, director Michael Mann has his own distinctive style, but what matters is how well he is able to use it to tell a story. Manhunter (1986), a solid and well-acted thriller, was tarnished by Mann's excessively "trendy" style, and a musical soundtrack that has kept the film perpetually trapped in the 1980s. More recently, Collateral (2004) demonstrated a precise and balanced combination of style and substance, making excellent use of the digital Viper FilmStream Camera, perfect for capturing the low-key lighting of Mann's favoured night-time urban landscape. His follow-up, Miami Vice (2006), was almost entirely devoid of substance, a meandering crime story redeemed only by a thrilling shoot-out in the final act. Heat (1995) is among Mann's most lauded achievements, and I'm happy to say that it's probably the finest of the director's films I've seen so far. Most noted for being the first film in which Al Pacino and Robert De Niro shared the same screen (they were separated by decades in Coppola's The Godfather: Part II (1974)), Heat is sizzling, action-packed drama.

Lt. Vincent Hanna (Al Pacino) is something of a cliché, the hard-working homicide detective who is distant from his family. However, Pacino gives the character depth, a hard-edged, street-wise cop who is basically good at heart. When writing dialogue for Al Pacino, the temptation is always there to make him shout a lot, and there are several scenes when Mann does exactly that, but the character is strongest when he's not talking at all, lost in silent contemplation or embracing the hysterical mother of a murder victim. Neil McCauley (Robert De Niro) sits on the opposite side of the law, a principled professional thief who has dedicated his entire life to crime. McCauley has a motto: "don't let yourself get attached to anything you are not willing to walk out on in 30 seconds flat if you feel the heat around the corner." His failure to adhere to this advice is ultimately what gets him killed, for, though he is prepared to discard his relationship with a sincere art designer (Amy Brenneman), McCauley unable to walk away from his own principles.

Lt. Vincent Hanna (Al Pacino) is something of a cliché, the hard-working homicide detective who is distant from his family. However, Pacino gives the character depth, a hard-edged, street-wise cop who is basically good at heart. When writing dialogue for Al Pacino, the temptation is always there to make him shout a lot, and there are several scenes when Mann does exactly that, but the character is strongest when he's not talking at all, lost in silent contemplation or embracing the hysterical mother of a murder victim. Neil McCauley (Robert De Niro) sits on the opposite side of the law, a principled professional thief who has dedicated his entire life to crime. McCauley has a motto: "don't let yourself get attached to anything you are not willing to walk out on in 30 seconds flat if you feel the heat around the corner." His failure to adhere to this advice is ultimately what gets him killed, for, though he is prepared to discard his relationship with a sincere art designer (Amy Brenneman), McCauley unable to walk away from his own principles. Heat boasts an impressive supporting cast – including Val Kilmer, Tom Sizemore, Dennis Haysbert and Jon Voight – but it's no surprise that Pacino and De Niro dominate the film. Their single face-to-face encounter is a corker, as they sit opposite each other sipping coffee (the table between them representing not only the border between police and criminal, but also a mirror of sorts). Hanna and McCauley exchange terse pleasantries like old friends, despite having never met before, and the two master actors coolly and effortlessly exude charisma with every word. The film's promotional tagline boasts "a Los Angeles crime saga," suggesting that Mann was attempting something akin to his own The Godfather (1972), though he doesn't quite pull it off as readily as Coppola. His film could have done with a few trimmings, excising a few largely superfluous personal subplots, including an impromptu suicide attempt that came right out of left-field. Nevertheless, Heat is a gripping crime story, with great performances, and one of the best shootouts that you'll see anywhere.

Heat boasts an impressive supporting cast – including Val Kilmer, Tom Sizemore, Dennis Haysbert and Jon Voight – but it's no surprise that Pacino and De Niro dominate the film. Their single face-to-face encounter is a corker, as they sit opposite each other sipping coffee (the table between them representing not only the border between police and criminal, but also a mirror of sorts). Hanna and McCauley exchange terse pleasantries like old friends, despite having never met before, and the two master actors coolly and effortlessly exude charisma with every word. The film's promotional tagline boasts "a Los Angeles crime saga," suggesting that Mann was attempting something akin to his own The Godfather (1972), though he doesn't quite pull it off as readily as Coppola. His film could have done with a few trimmings, excising a few largely superfluous personal subplots, including an impromptu suicide attempt that came right out of left-field. Nevertheless, Heat is a gripping crime story, with great performances, and one of the best shootouts that you'll see anywhere.

8/10

Currently my #3 film of 1995:

1) Twelve Monkeys (Terry Gilliam)

2) Se7en (David Fincher)

3) Heat (Michael Mann)

4) GoldenEye (Martin Campbell)

5) La Cité des enfants perdus {The City of Lost Children} (Marc Caro, Jean-Pierre Jeunet)

6) Braveheart (Mel Gibson)

7) Apollo 13 (Ron Howard)

8) Babe (Chris Noonan)

9) Die Hard: With a Vengeance (John McTiernan)

10) Toy Story (John Lasseter)

Saturday, December 20, 2008

Target #251: Get Carter (1971, Mike Hodges)

TSPDT placing: #570

Directed by: Mike Hodges

Written by: Ted Lewis (novel), Mike Hodges (screenplay)

Starring: Michael Caine, Ian Hendry, Britt Ekland, John Osborne, Tony Beckley, George Sewell, Geraldine Moffat

WARNING: Plot and/or ending details may follow!!! [Paragraph 2 only]

1971 was the year when mainstream filmmakers began to the push the limits of what was acceptable to show on screen, both in terms of sex and violence. Stanley Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange (1971) enthralled and disgusted audiences on both sides of the Atlantic, picking up a surprise Oscar nomination for Best Picture but later being voluntarily withdrawn from circulation by its director. Sam Peckinpah's Straw Dogs (1971) shocked audiences with its uncompromising exploration of inherent human violence and vigilantism. Likewise, Get Carter (1971), from director Mike Hodges, is an incredibly gritty underworld gangster film, so much so that you can almost taste the gravel between your teeth. It won't escape your notice that all three of these films are British, or, at least, were produced with substantial British input; apparently, it took Hollywood a few more years to become quite as well accustomed to such themes, though that year's Best Picture-winner, The French Connection (1971), does rival Get Carter as far as grittiness goes.

Jack Carter (Michael Caine) is a London gangster, an entirely unglamorous occupation that entails such duties as gambling, murder and watching pornography. After his brother, Frank, dies in Newcastle under suspicious circumstances, Jack goes up there, against the wishes of his employer, to find out exactly what happened, and to punish all those responsible. What he finds is the usual assortment of sleazy low-lifes and lascivious whores, all part of the underground lifestyle into which he sold himself. Get Carter obviously derived a degree of influence from the trashy pulp-fiction novels of Raymond Chandler and Mickey Spillane, and, indeed, this inspiration is openly acknowledged when Carter is seen reading "Farewell My Lovely" {adapted by Edward Dmytryk as Murder, My Sweet (1944)}. Like many of the hard-boiled anti-heroes of 1940s and 50s film noir, he has sold his soul for a chance at revenge, and there's no going back. A detail worth noting is that Carter's eventual assassin is first spotted in the opening credits, sitting opposite in the train carriage. A cruel coincidence, or was his fate sealed from the very beginning?

Jack Carter (Michael Caine) is a London gangster, an entirely unglamorous occupation that entails such duties as gambling, murder and watching pornography. After his brother, Frank, dies in Newcastle under suspicious circumstances, Jack goes up there, against the wishes of his employer, to find out exactly what happened, and to punish all those responsible. What he finds is the usual assortment of sleazy low-lifes and lascivious whores, all part of the underground lifestyle into which he sold himself. Get Carter obviously derived a degree of influence from the trashy pulp-fiction novels of Raymond Chandler and Mickey Spillane, and, indeed, this inspiration is openly acknowledged when Carter is seen reading "Farewell My Lovely" {adapted by Edward Dmytryk as Murder, My Sweet (1944)}. Like many of the hard-boiled anti-heroes of 1940s and 50s film noir, he has sold his soul for a chance at revenge, and there's no going back. A detail worth noting is that Carter's eventual assassin is first spotted in the opening credits, sitting opposite in the train carriage. A cruel coincidence, or was his fate sealed from the very beginning? Get Carter may have served as inspiration to the recent generation of British gangster film, but the Quentin Tarantino/Guy Ritchie style of film-making favoured today – the most notable example of which being Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels (1998) – is often excessively trendy and highly stylised. Mike Hodges' idea of a gangster film is ugly – disgustingly and uncomfortably repellent, offering not a glimmer of respectability nor nobility in its selection of depraved characters. Even Jack Carter himself is not a man we are asked to admire. He may have a steady supply of droll one-liners at hand, but at his heart he is cold, almost completely devoid of human emotion. Just watch Carter's stone-face as his car is rammed into the bay (with an unfortunate captive in the boot), or his indifference to the fate of friend Keith (Alun Armstrong), who is thoroughly roughed-up while lending a hand. Hodges appears only to find decency in the deceased Frank, who represents the honest, working-class type of man. However, even this legacy is coming to an end, for the next generation, Doreen, has already been corrupted.

Get Carter may have served as inspiration to the recent generation of British gangster film, but the Quentin Tarantino/Guy Ritchie style of film-making favoured today – the most notable example of which being Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels (1998) – is often excessively trendy and highly stylised. Mike Hodges' idea of a gangster film is ugly – disgustingly and uncomfortably repellent, offering not a glimmer of respectability nor nobility in its selection of depraved characters. Even Jack Carter himself is not a man we are asked to admire. He may have a steady supply of droll one-liners at hand, but at his heart he is cold, almost completely devoid of human emotion. Just watch Carter's stone-face as his car is rammed into the bay (with an unfortunate captive in the boot), or his indifference to the fate of friend Keith (Alun Armstrong), who is thoroughly roughed-up while lending a hand. Hodges appears only to find decency in the deceased Frank, who represents the honest, working-class type of man. However, even this legacy is coming to an end, for the next generation, Doreen, has already been corrupted.7.5/10

Currently my #5 film of 1971:

1) A Clockwork Orange (Stanley Kubrick)

2) Straw Dogs (Sam Peckinpah)

3) Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory (Mel Stuart)

4) The French Connection (William Friedkin)

5) Get Carter (Mike Hodges)

Tuesday, September 23, 2008

Target #233: Shock Corridor (1963, Samuel Fuller)

TSPDT placing: #715

Directed by: Samuel Fuller

Written by: Samuel Fuller

Starring: Peter Breck, Constance Towers, Gene Evans, James Best, Hari Rhodes, Larry Tucker, Paul Dubov

Like any good B-movie should, Shock Corridor (1963) builds itself upon a shaky and unlikely premise. Johnny Barrett (Peter Breck, who reminds me of a young Martin Sheen) is a hot-shot journalist with aspirations towards the Pullitzer Prize. In order to crack an unsolved murder in a psychiatric hospital, Barrett offers to have himself committed, fooling police and doctors into believing that he has made incestuous advantages towards his sister– actually his long-time girlfriend, Cathy (Constance Towers). There are, of course, unaddressed hurdles in this ridiculous scheme: why would the authorities never bother to verify Cathy's true identity? However, once Barrett gets inside the mental ward, we're so fascinated by its peculiar brand of loonies that we don't ask any further questions. The supporting performances vary greatly in subtlety and credibility, but there's no doubt that they hold our attention, prone to unexpected violent outbursts and momentary reclamation of their sanity. Barrett's murder investigation is straightforward and episodic: he merely befriends each of the three witnesses in turn, and waits for them to come to their senses.

Like any good B-movie should, Shock Corridor (1963) builds itself upon a shaky and unlikely premise. Johnny Barrett (Peter Breck, who reminds me of a young Martin Sheen) is a hot-shot journalist with aspirations towards the Pullitzer Prize. In order to crack an unsolved murder in a psychiatric hospital, Barrett offers to have himself committed, fooling police and doctors into believing that he has made incestuous advantages towards his sister– actually his long-time girlfriend, Cathy (Constance Towers). There are, of course, unaddressed hurdles in this ridiculous scheme: why would the authorities never bother to verify Cathy's true identity? However, once Barrett gets inside the mental ward, we're so fascinated by its peculiar brand of loonies that we don't ask any further questions. The supporting performances vary greatly in subtlety and credibility, but there's no doubt that they hold our attention, prone to unexpected violent outbursts and momentary reclamation of their sanity. Barrett's murder investigation is straightforward and episodic: he merely befriends each of the three witnesses in turn, and waits for them to come to their senses. This being my first film from Samuel Fuller, I'm not sure whether or not his films typically have underlying political messages. However, Shock Corridor is certainly a confronting critique of the American mental health system; indeed, how can the mentally ill ever recover if even a sane man loses his sanity after just several months in such an institution? I was tempted to think that Barrett's mental deterioration was based on the findings of the disastrous Stanford Prison Experiment, in which human behaviour was drastically influenced by one's appointed status as either a "guard" or a "prisoner." Then I remembered that Zimbardo's study wasn't undertaken until 1971, which makes Fuller's conclusions even more audacious and groundbreaking. The film was shot by cinematographer Stanley Cortez, who also worked on The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) and The Night of the Hunter (1955), who superbly blends the raw, gritty aesthetic of low-budget schlock with the surreal, distorted visuals of big-budget film noir. Call it bold, call it outrageous, call it ridiculous –but there's no doubting that Sam Fuller is a director to watch.

This being my first film from Samuel Fuller, I'm not sure whether or not his films typically have underlying political messages. However, Shock Corridor is certainly a confronting critique of the American mental health system; indeed, how can the mentally ill ever recover if even a sane man loses his sanity after just several months in such an institution? I was tempted to think that Barrett's mental deterioration was based on the findings of the disastrous Stanford Prison Experiment, in which human behaviour was drastically influenced by one's appointed status as either a "guard" or a "prisoner." Then I remembered that Zimbardo's study wasn't undertaken until 1971, which makes Fuller's conclusions even more audacious and groundbreaking. The film was shot by cinematographer Stanley Cortez, who also worked on The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) and The Night of the Hunter (1955), who superbly blends the raw, gritty aesthetic of low-budget schlock with the surreal, distorted visuals of big-budget film noir. Call it bold, call it outrageous, call it ridiculous –but there's no doubting that Sam Fuller is a director to watch.2) Irma la Douce (Billy Wilder)

3) The Birds (Alfred Hitchcock)

4) From Russia with Love (Terence Young)

5) 8½ (Federico Fellini)

6) Shock Corridor (Samuel Fuller)

What others have said:

What others have said:Friday, August 22, 2008

Repeat Viewing: Touch of Evil (1958, Orson Welles)

TSPDT placing: #22

Also recommended from director Orson Welles:

Also recommended from director Orson Welles:

Saturday, August 2, 2008

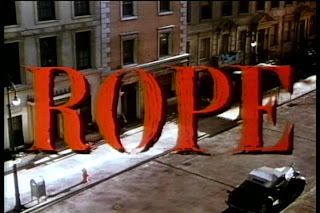

Repeat Viewing: Rope (1948, Alfred Hitchcock)

TSPDT placing: #955

Alfred Hitchcock, despite his commercial popularity, was perhaps one of cinema's most audacious technical innovators. Even very early in his career – Blackmail (1929) was the first British film to make the cross-over into "talkies" – the Master of Suspense was forever searching for distinctive new means of telling a story and furthering his craft. Hitchcock was particularly interested in film-making that unfolded almost exclusively in a single restricted location, perhaps because of its likeness to a traditional stage play, or, more tellingly, because it allowed him to place the audience "in the room" with his nefarious characters. The director's first such endeavour was the radical Lifeboat (1944), which took place entirely on a small boat in the middle of the Atlantic, and similar "one-room" thrillers include Dial M for Murder (1954) and Rear Window (1954). Of course, the most experimental of these experiments was undoubtedly Rope (1948), a tense and intimate suspense tale that utilised extraordinarily-long takes to unfold the story almost in real-time. Against all odds, it's one of Hitchcock's finest.

Alfred Hitchcock, despite his commercial popularity, was perhaps one of cinema's most audacious technical innovators. Even very early in his career – Blackmail (1929) was the first British film to make the cross-over into "talkies" – the Master of Suspense was forever searching for distinctive new means of telling a story and furthering his craft. Hitchcock was particularly interested in film-making that unfolded almost exclusively in a single restricted location, perhaps because of its likeness to a traditional stage play, or, more tellingly, because it allowed him to place the audience "in the room" with his nefarious characters. The director's first such endeavour was the radical Lifeboat (1944), which took place entirely on a small boat in the middle of the Atlantic, and similar "one-room" thrillers include Dial M for Murder (1954) and Rear Window (1954). Of course, the most experimental of these experiments was undoubtedly Rope (1948), a tense and intimate suspense tale that utilised extraordinarily-long takes to unfold the story almost in real-time. Against all odds, it's one of Hitchcock's finest.

All this action unfolds through ten continuous long takes, of between four and ten minutes in length, with around half of the transitions made "invisible" by dollying forward into the darkness of a character's back. As the characters move back and forth across Hitchcock's set, their lines and movements precisely choreographed, the cameramen and sound recordists track smoothly with them, constantly moving props and furniture out of the path of the filming equipment. This was the first occasion that such an audacious film-making technique had been trialled, and Rope wouldn't be bettered until digital technology allowed Aleksandr Sokurov to film the entirety of Russian Ark (2002) in a single take. Some have subsequently termed Hitchcock's film to be nothing but a gimmick, but to do so would be grossly unfair to all involved – indeed, when I first viewed the film, such was my immersion in the story that, unbelievably enough, it took me the bulk of the running time to even notice that I was watching unbroken takes.

2) Ladri di biciclette {The Bicycle Thief} (Vittorio De Sicae)

3) Rope (Alfred Hitchcock)

4) Oliver Twist (David Lean)

5) Macbeth (Orson Welles)

What others have said:

What others have said:Monday, July 28, 2008

Target #227: Laura (1944, Otto Preminger)

TSPDT placing: #320

Directed by: Otto Preminger, Rouben Mamoulian (uncredited)

WARNING: Plot and/or ending details may follow!!! [Paragraph 3 Only]

WARNING: Plot and/or ending details may follow!!! [Paragraph 3 Only] There is no other way to say it: Gene Tierney is absolutely ravishing. From the film's opening moments, when we glimpse her seductive figure in a hanging portrait, my heart melted; I was instantly brought under her enchanting spell. If I may adopt the vocabulary of our hard-boiled hero, she's a perfect dame! When hard-edged cop Mark McPherson (Dana Andrews, the spitting image of Steve Martin in Dead Men Don't Wear Plaid (1982)) is assigned to investigate the brutal murder of the city's most coveted women (Tierney), he uncovers a bizarre romantic triangle that offers endless motives for such a heinous crime. Waldo Lydecker (Clifton Webb), an older newspaper columnist with a reputation for acid wit, originally offered Laura her big break in business, and had protectively maintained a relationship with her that surpassed love and bordered on obsession. Meanwhile, a wealthy charmer, Shelby Carpenter (Vincent Price), had asked for Laura's hand in marriage, a proposal about which she had been non-committal. Even in death, Laura's femme fatale charm remains just as potent, and Lt. McPherson soon finds himself infatuated with her lingering spirit.

There is no other way to say it: Gene Tierney is absolutely ravishing. From the film's opening moments, when we glimpse her seductive figure in a hanging portrait, my heart melted; I was instantly brought under her enchanting spell. If I may adopt the vocabulary of our hard-boiled hero, she's a perfect dame! When hard-edged cop Mark McPherson (Dana Andrews, the spitting image of Steve Martin in Dead Men Don't Wear Plaid (1982)) is assigned to investigate the brutal murder of the city's most coveted women (Tierney), he uncovers a bizarre romantic triangle that offers endless motives for such a heinous crime. Waldo Lydecker (Clifton Webb), an older newspaper columnist with a reputation for acid wit, originally offered Laura her big break in business, and had protectively maintained a relationship with her that surpassed love and bordered on obsession. Meanwhile, a wealthy charmer, Shelby Carpenter (Vincent Price), had asked for Laura's hand in marriage, a proposal about which she had been non-committal. Even in death, Laura's femme fatale charm remains just as potent, and Lt. McPherson soon finds himself infatuated with her lingering spirit.  Then, of course, comes the wonderfully-surreal moment when our love-struck detective awakens to watch his murder victim walk into the room. Originally, Rouben Mamoulian {Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931)} had been hired to direct the film, and his version ended with the revelation that Laura's reappearance had merely been a dream, a construction of McPherson's subconscious. When producer Otto Preminger decided to take over, he unceremoniously scrapped Mamoulian's completed footage and started over. Even without this final psychological complication, which might nevertheless have seemed a cop-out, Preminger's mystery is consistently engrossing and often fascinating. Most intriguing of all is Lydecker's relationship with Laura, and Clifton Webb's unconventional yet highly-effective casting in the role. The noted Broadway performer had not acted in a film since the silent era, but his flamboyant and foppish personality translates perfectly to the screen. Lydecker doesn't seem to actually love Laura, but rather he wishes to be her, to live vicariously through her, and for any man (other than himself) to be in Laura's life is an affront both to himself and his sexuality.

Then, of course, comes the wonderfully-surreal moment when our love-struck detective awakens to watch his murder victim walk into the room. Originally, Rouben Mamoulian {Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931)} had been hired to direct the film, and his version ended with the revelation that Laura's reappearance had merely been a dream, a construction of McPherson's subconscious. When producer Otto Preminger decided to take over, he unceremoniously scrapped Mamoulian's completed footage and started over. Even without this final psychological complication, which might nevertheless have seemed a cop-out, Preminger's mystery is consistently engrossing and often fascinating. Most intriguing of all is Lydecker's relationship with Laura, and Clifton Webb's unconventional yet highly-effective casting in the role. The noted Broadway performer had not acted in a film since the silent era, but his flamboyant and foppish personality translates perfectly to the screen. Lydecker doesn't seem to actually love Laura, but rather he wishes to be her, to live vicariously through her, and for any man (other than himself) to be in Laura's life is an affront both to himself and his sexuality.2) Arsenic and Old Lace (Frank Capra)

3) Gaslight (George Cukor)

4) Laura (Otto Preminger)

5) Lifeboat (Alfred Hitchcock)

What others have said:

What others have said:Wednesday, July 23, 2008

Target #225: The Innocents (1961, Jack Clayton)

TSPDT placing: #552

WARNING: Plot and/or ending details may follow!!!

WARNING: Plot and/or ending details may follow!!!

2) One, Two, Three (Billy Wilder)

What others have said:

What others have said: Also recommended:

Also recommended:

_poster.jpg)