TSPDT placing: #913

Directed by: Frank Borzage

Written by: Austin Strong, Benjamin Glazer (screenplay), H.H. Caldwell (titles), Katherine Hilliker (titles), Bernard Vorhaus

Starring: Janet Gaynor, Charles Farrell, Ben Bard, Albert Gran, David Butler, Marie Mosquini, George E. Stone

WARNING: Plot and/or ending details may follow!!! [Paragraph 3 only]

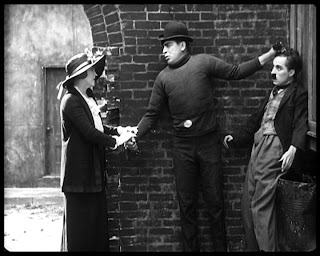

Seventh Heaven (1927) is usually compared to Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927), and not without reason. Director Frank Borzage has a keen sense for lighting and shot composition, perhaps not as effortlessly graceful as that of Murnau, but the film superbly explores three-dimensional space, most memorably in a vertical long take that follows the characters up seven floors of staircases, and a backwards tracking shot through the crowded trenches of a battlefield. Janet Gaynor, who also starred in Sunrise, is once again a perfect picture of fragility and helplessness, a persona at which she was bettered only by Lillian Gish. More interesting, however, is that Gaynor's character undergoes a startling character arc, developing from a weak, embattled victim – a trampled flower – to a decisive and assertive woman, a member of the workforce, and an independent but devoted wife. Her husband, played by Charles Farrell, likewise undergoes a transformation, of the spiritual kind. Together, they share a love so definitive that the formula has since become familiar, but Borzage keeps it fresh. Perhaps the greatest miracle about Seventh Heaven is that the romance works at all. Farrell's Chico is a haughty, athletic sewer worker, so determined of his own worth that he bores his grotesque colleagues with anecdotes of his future greatness. Gaynor's Diane, a small creature routinely lashed by her sleazy sister, is at first an object of derision for Chico, who uses her mere existence to affirm his atheism. Indeed, so aloof is his attitude towards her that I could scarcely believe that the pair were to fall in love, but the transition is carried out gradually and convincingly. As in most great romances, the two star-crossed lovers are swiftly separated by the onset of war. Here, once again, Borzage's keen eye for visual storytelling results in some wonderful sequences of conflict, with his portrayal of the battlefield perhaps serving as inspiration for Lewis Milestone's war drama All Quiet on the Western Front (1930). Only with the occasional moments of misplaced comedy – the ritualistic bowing of the street-sweepers, for example – does the director fumble with the film's mood.

Perhaps the greatest miracle about Seventh Heaven is that the romance works at all. Farrell's Chico is a haughty, athletic sewer worker, so determined of his own worth that he bores his grotesque colleagues with anecdotes of his future greatness. Gaynor's Diane, a small creature routinely lashed by her sleazy sister, is at first an object of derision for Chico, who uses her mere existence to affirm his atheism. Indeed, so aloof is his attitude towards her that I could scarcely believe that the pair were to fall in love, but the transition is carried out gradually and convincingly. As in most great romances, the two star-crossed lovers are swiftly separated by the onset of war. Here, once again, Borzage's keen eye for visual storytelling results in some wonderful sequences of conflict, with his portrayal of the battlefield perhaps serving as inspiration for Lewis Milestone's war drama All Quiet on the Western Front (1930). Only with the occasional moments of misplaced comedy – the ritualistic bowing of the street-sweepers, for example – does the director fumble with the film's mood. This reviewer being an atheist, films dealing with a central religious theme face an uphill battle. Chico opens the film not unlike myself, as an obstinate atheist who curses God for failing to answer his prayers. Christianity intercedes through a kind-hearted priest, who offers Chico his dream-job as a street-sweeper, as well as two religious necklaces. Predictably, our hero is converted by the film's end, and, indeed, stages a resurrection that borders on Biblical. This "miraculous" ending could easily have had me rolling my eyes, but – somehow, and against all odds – it didn't. Borzage doesn't play Chico's survival as a startling revelation, and nor does it feel tacked-on, as does the fate of Murnau's hotel doorman in The Last Laugh (1924). Alongside Diane's stubborn insistence that her husband is still alive, to actually see him pushing through the crowds seemed like the most natural thing in the world. And even if Chico is dead, then his wife is already there in Heaven, on the seventh floor, waiting to greet him.

This reviewer being an atheist, films dealing with a central religious theme face an uphill battle. Chico opens the film not unlike myself, as an obstinate atheist who curses God for failing to answer his prayers. Christianity intercedes through a kind-hearted priest, who offers Chico his dream-job as a street-sweeper, as well as two religious necklaces. Predictably, our hero is converted by the film's end, and, indeed, stages a resurrection that borders on Biblical. This "miraculous" ending could easily have had me rolling my eyes, but – somehow, and against all odds – it didn't. Borzage doesn't play Chico's survival as a startling revelation, and nor does it feel tacked-on, as does the fate of Murnau's hotel doorman in The Last Laugh (1924). Alongside Diane's stubborn insistence that her husband is still alive, to actually see him pushing through the crowds seemed like the most natural thing in the world. And even if Chico is dead, then his wife is already there in Heaven, on the seventh floor, waiting to greet him.

7.5/10

Currently my #4 film of 1927:

1) Metropolis (Fritz Lang)

2) Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (F.W. Murnau)

3) The General (Clyde Bruckman, Buster Keaton)

4) 7th Heaven (Frank Borzage)

5) College (James W. Horne, Buster Keaton)

6) The Lodger (Alfred Hitchcock)

Friday, June 5, 2009

Target #272: Seventh Heaven (1927, Frank Borzage)

Sunday, March 22, 2009

Repeat Viewing: Modern Times (1936, Charles Chaplin)

TSPDT placing: #48

Chaplin may also have been remarking upon the rise of the Hollywood studio system, which by then employed a comparable assembly-line approach to film-making. Chaplin, who was given full artistic control through his co-ownership of United Artists, worked in complete opposition to these practices, though it could be argued that his perfectionism and often improvisational style was so inefficient that only an artist as wealthy as he could have gotten away with it. Truth be told, there's nothing particularly distinguished about Chaplin's direction – despite his strong reliance upon actions over words, his silent films were never as visually accomplished as that of Murnau or Lang, for example. However, his greatest talents as a filmmaker were concerned with the plight of people, and, however much sentimentality he liked to dish out, there can be no doubt that, in Chaplin's characters, one found individuals with whom they shared a very real human bond, of empathy and compassion. For all the director's criticism of modern society, he possessed a genuine belief in the value of human spirit.

2) After the Thin Man (W.S. Van Dyke)

3) Swing Time (George Stevens)

4) Partie de campagne {A Day in the Country} (Jean Renoir)

5) Follow the Fleet (Mark Sandrich)

6) Sabotage (Alfred Hitchcock)

7) Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (Frank Capra)

8) Secret Agent (Alfred Hitchcock)

9) Intermezzo (Gustaf Molander)

10) My Man Godfrey (Gregory La Cava)

Thursday, August 7, 2008

Target #228: Our Hospitality (1923, John G. Blystone, Buster Keaton)

TSPDT placing: #359

2) Safety Last! (Fred C. Newmeyer, Sam Taylor)

3) Our Hospitality (Buster Keaton, John G. Blystone)

4) The Pilgrim (Charles Chaplin)

5) Why Worry? (Fred C. Newmeyer, Sam Taylor)

What others have said:

What others have said: Also recommended from Buster Keaton:

Also recommended from Buster Keaton:

Saturday, June 28, 2008

Target #217: The Kid (1921, Charles Chaplin)

TSPDT placing: #261

Directed by: Charles Chaplin

Written by: Charles Chaplin

Starring: Charles Chaplin, Jackie Coogan, Edna Purviance, Carl Miller, John McKinnon, Charles Reisner

Charles Chaplin was born on April 16, 1889, in East Street, Walworth, London. Though his parents, both music hall entertainers, separated before his third birthday, they also raised him into the entertainment business. His first appearance on film was in Making a Living (1914), a one-reel comedy released on February 2, 1914. It didn't take long for Chaplin to find his niche in the film-making industry, and his character of the Tramp – who first appeared in Kid Auto Races at Venice (1914) – guaranteed his popularity and longevity in the industry. After a string of successful short films, among the most accomplished of which are Shoulder Arms (1918) and A Dog's Life (1918), Chaplin commenced production on his first feature-length outing with the Tramp. The Kid (1921) proved an instant success, becoming the second highest-grossing film of 1921 {behind Rex Ingram's The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921)} and ensuring another fifteen years of comedies featuring Chaplin's most enduring character.

The Kid opens in somewhat sombre circumstances, as a struggling entertainer (Chaplin regular Edna Purviance) emerges from the hospital clasping her unwanted child. Unable, or perhaps unwilling, to care for the infant, she regretfully abandons the baby in an automobile, which is promptly hijacked by unscrupulous criminals. The car thieves discard the orphan in a garbage-strewn alleyway, at which point our humble vagrant hero comes tramping down the street. Upon his discovery of the little bundle-of-joy, Chaplin demonstrates the most practical response, and glances inquiringly upwards, both at the apartment windows through which residents like to toss their leftovers, and at the Heavens, who conceivably might have dropped a newborn from the sky. After several awkward attempts to unload the baby on somebody else, Chaplin lovingly decides to raise the kid himself, crudely fashioning the necessities of child-raising (a milk bottle, a toilet seat) from his own modest possessions. Five years on, the Kid (Jackie Coogan) has blossomed into a devoted and energetic sidekick, a partner-in-crime if you will, and it is then that Chaplin's fatherhood is placed in jeopardy.

The Tramp's young co-star was the son of an actor, and Chaplin first discovered him during a vaudeville performance, when the four-year-old entertained audiences with the "shimmy," a popular dance at the time. Chaplin was delighted with Coogan's natural talent for mimicry, and his ability to precisely impersonate the Tramp's unique expressions and mannerisms – becoming, in effect, a childhood version of Chaplin – was crucial to the film's success. The domestic bond exhibited by the pair is faultless in every regard, and, adding to the poignancy of their relationship, Chaplin began work on the production just days after the death of his own three-day-old newborn son, Norman Spencer Chaplin (during his short-lived marriage to child actor Mildred Harris). The mutual compassion and understanding underlying the central father-son relationship remains very touching nearly ninety years later, particularly when the pair employ their combined talents to promote the continued prolificacy of the Tramp's window-repair business. However, even during proceedings as ordinary as a pancake breakfast, that the two share a genuine affection for one another is beyond question.

According to Chaplin's autobiography, actor Jack Coogan, Sr (who plays several minor roles throughout the film, including the troublesome Devil in the dream sequence) told his young son that, if he couldn't cry convincingly, he'd be sent to a workhouse for real. We can never know for certain if this was the case, but what we do know is that, during the separation sequence, young Coogan delivers one of the most heart-wrenching child performances ever committed to the screen, his hands stretched outwards in a grief-stricken plea for mercy. His performance is intercut with Chaplin grappling frantically with the authorities, his widened eyes staring directly at the camera, as though actively pleading for the audience's sympathy and assistance; it's one of the director's all-time most unforgettable moments, and first decisive instance that Chaplin was able to so seamlessly blend humour and pathos. In the 1970s, Chaplin – ever the perfectionist – re-released the film with a newly-composed score, and deleted three additional sequences involving Purviance as the orphan's mother, which might explain why the kid's father (Carl Miller) apparently serves no use to the story.

8/10

Currently my #2 film of 1921:

1) Körkarlen {The Phantom Chariot} (Victor Sjöström)

2) The Kid (Charles Chaplin) Currently my #10 film from director Charles Chaplin:

Currently my #10 film from director Charles Chaplin:

1) Modern Times (1936)

2) The Great Dictator (1940)

3) City Lights (1931)

4) Limelight (1952)

5) The Gold Rush (1925)

6) Monsieur Verdoux (1947)

7) A Woman of Paris: A Drama of Fate (1923)

8) Shoulder Arms (1918)

9) A King in New York (1957)

10) The Kid (1921)

Also on the TSPDT top 1000:

#21 - City Lights (1931)

#34 - The Gold Rush (1925)

#52 - Modern Times (1936)

#176 - Monsieur Verdoux (1947)

#252 - The Great Dictator (1940)

#403 - Limelight (1952)

#455 - The Circus (1928)

#753 - The Pilgrim (1923)

#876 - A Woman of Paris (1923)

“Chaplin and Coogan are so in synch here that it's believable that they really are father and son, and others on the set report that Chaplin really did treat the young actor like his son during the prolonged shoot. Like clones from two generations, Chaplin and Coogan successfully bring off virtually perfect comic scenes that come across naturally, but it's the "sentimental" scene that everyone remembers…. The pure anguish that both Coogan and Chaplin display during the separation scene feels so real that we could be watching a documentary paralleling the workhouse days of Dickens' London. Coogan's tears, outstretched arms, and silent wailing all communicate total devastation as do the cuts to Chaplin's underplayed looks of horror and desperation. Combined together, it's a sequence that lives on forever and continually is replayed in Chaplin highlights.”

John Nesbit

“While losing his son undoubtedly reawakened those old boyhood memories, their artistic rendering took place with Charlie's heart, not his head. And the idea probably succeeds because it is largely unconscious rather than self-conscious autobiography…Taking the lowbrow slapstick route, he quarried for bits and shticks, not archetypes and myths. But funny things can happen on that low road to comedy, just as they do on the high road to tragedy. Just as Oedipus and Laius--father and son--encounter each other by chance at one of life's crossroads, so Charlie the fatherless kid and Chaplin the childless father accidentally meet in a London lane. Unlike their ancient predecessors, whose hearts are filled with mistrust and hate, Charlie Chaplin and the lost child are filled with yearning and affection. And so their tale is a bittersweet ballad of love and loss. Griminess is next to Godliness in a comic universe where the disinherited can inherit the earth.”

Stephen M. Weissman

“Unless your heart is as stony as a biblical execution, I challenge you to watch unmoved as Charlie Chaplin's heroic vagabond rescues five-year-old Jackie Coogan from being hauled away to the "orphan asylum." At this point in The Kid, Chaplin's musical score tugs any heartstrings not yet plucked by the look on the Kid's face as he pleads for release, or on the Tramp's as he victoriously embraces the foundling child. Say what you will about Chaplin's deployment of pathos (you can almost see him pulling the pin with his teeth and lobbing it into our laps), this scene in "a picture with a smile and perhaps a tear" is one of those glorious movie moments that demonstrates what the medium can do when the right emotionally haunted, increasingly self-absorbed, control-freak genius is calling the shots.”

Mark Bourne

"Written, produced and directed by Chaplin, A Woman of Paris is a tightly-paced drama/romance, employing a lot of dialogue (somewhat unusual for Chaplin, who usually relied on extended slapstick comedic set pieces to drive his silent films) and a three-way relationship that has since become commonplace in films of this sort. The film allowed Chaplin to extend his skills beyond the realm of the lovable little Tramp. Unfortunately, this seemingly was not what audiences wanted. Perhaps perceived as a harmful satire of the American way of life, A Woman of Paris was banned in several US states on the grounds of immorality, and it was a commercial flop. Chaplin had conceived the film as a means of launching the individual acting career of Edna Purviance, though this bid was unsuccessful. It did, however, make an international star of Adolphe Menjou."

"Despite the absence of any real emotion in The Pilgrim, Chaplin's film still succeeds on its own terms, with the criminal's situation allowing for an assortment of amusing scenarios. Dressed as a parson, one is always expected to act in the most civilised fashion, and yet our poor hero finds that he just can't play the part. Chaplin's incredible skill for visual communication is most stunningly apparent in his character's gesticulated re-telling of the David vs Goliath legend, and, without the aid of sound, the audience can easily follow every single detail of the story. Also hilarious are the Pilgrim's attempts at making a cake {using the hat belonging to Chaplin's brother and co-star, Syd}, his response to the antics of Howard Huntington the dishonest thief, and his inability to take a policeman's hint beside the border into Mexico."

"A Dog's Life was Chaplin's first film for First National Films, a company founded in 1917 by the merger of 26 of the biggest first-run cinema chains... What is perhaps most impressive about the film is the way in which Chaplin parallels the daily struggles of the Tramp with those of the young dog, Scraps, a Thoroughbred Mongrel... In support of the old adage that good will always be rewarded with good, Chaplin comes to the aid of Scraps when he is being attacked by a gang of predatory dogs, and, in return, the intelligent canine ultimately retrieves the means by which our hero may retire into the country with his sweetheart (Edna Purviance). As in The Pilgrim, the chemistry between Purviance and Chaplin is somewhat unconvincing, but she does elicit a fair amount of empathy in her portrayal of an exploited and cruelly-treated bar singer."

Monday, June 23, 2008

Target #213: Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927, F.W. Murnau)

TSPDT placing: #10

Directed by: F.W. Murnau

Written by: Hermann Sudermann (novella), Carl Mayer (scenario), Katherine Hilliker, H.H. Caldwell (titles)

Starring: George O'Brien, Janet Gaynor, Margaret Livingston, Bodil Rosing, J. Farrell MacDonald, Ralph Sipperly

WARNING: Plot and/or ending details may follow!!!

Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927) is simply one of the most breathtaking motion pictures of the silent era, and certainly one of the most effective to have originated in Hollywood. However, the film's creative talent arrived from overseas, when William Fox, founder of the Fox Films Corporation, lured prominent German director F.W. Murnau over to the United States with the promise of a greater budget and complete artistic freedom. Murnau, who had previously brought German Expressionism to its creative peak with Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens (1922) and Faust - Eine deutsche Volkssage (1926), spared no expense at his new American studio, and the result is quite possibly his most extraordinary storytelling achievement, blending reality and fantasy into a wonderfully-balanced melodramatic fable of love and redemption. Though inevitably overshadowed by the arrival of "talkies" with The Jazz Singer (1927), the film was also the first to utilize the Fox Movietone sound-on-film system, which allowed the inclusion of roughly-synchronised music, sound effects and a few garbled voices.

Just as he did in Der letzte Mann (1924), Murnau makes sparing use of intertitles, and so the film relies heavily on visuals in order to propel the story and invoke the desired mood. During his mercilessly short-lived career, the German director subscribed to two distinct film-making styles: German Expressionism, which deliberately exaggerated geometry and lighting for symbolic purposes, and the short-lived Kammerspiel ("chamber-drama") genre, most readily noticed in The Last Laugh, which bordered on neo-realistic at times, but also pioneered the moving camera in order to capture the intimacy of a character's point-of-view. Sunrise appears to have been influenced by both styles. The fable of The Man (George O'Brien) and The Wife (Janet Gaynor), its time and place purposefully vague, fittingly takes place in a plane of reality not quite aligned with our own, without straying too perceptibly into the realm of fantasy. Murnau also had mammoth sets created for the city sequences, fantastically stylised and exaggerated to re-enforce the picture's fairytale ambiance.

The characters in Sunrise are best viewed as representatives of archetypes, performing a very specific function in Murnau's moral parable. The story's primary themes are forgiveness and redemption. The Man, a misguided fool torn between two lovers, is driven to the brink of murder, but manages to stop himself at the final moment. The remainder of the film involves The Man's attempts at, not only understanding the gravity of what might have been, but also to recall his former love for his wife. I can't imagine what camera filters must have been used to transform Janet Gaynor into the supreme personification of innocence and vulnerability, but she is the most heartbreakingly-helpless figure since Lillian Gish in Broken Blossoms (1919). Even so, for the bulk of the film, the power to reconcile their estranged marriage lies solely within the hands of The Wife, whose role in the story is to recognise the remorse of her husband, and, in accordance with their sacred wedding vows, to forgive him his shameful transgressions.

The development of the moving camera was a crucial step towards the dynamic style of cinema that we now enjoy. Though the first notable use of the technique was in The Last Laugh, and Murnau is said to have used it even earlier, some of the sequences in Sunrise are simply beyond words in their gracefulness and beauty. In easily the most memorable long-take of the film, and perhaps even the decade, Karl Struss and Charles Rosher's camera sweeps behind The Man as he makes his way through the moon-lit scrub-land, before overtaking him, passing through a swathe of tree branches and arriving at The Women From the City (Margaret Livingston), who applies her make-up and waits for the married suitor whom she is about to convince to murder his wife. I first caught a split-second glimpse of this wonderful shot in Chuck Workman's montage short, Precious Images (1986), and it's a telling sign that, of all the four hundred or so movies briefly exhibited in that film, it was this one that caught my eye.

9/10

Currently my #2 film of 1927:

1) Metropolis (Fritz Lang)

2) Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (F.W. Murnau)

3) The General (Clyde Bruckman, Buster Keaton)

4) College (James W. Horne, Buster Keaton

5) The Lodger (Alfred Hitchcock) Currently my #1 film from director F.W. Murnau:

Currently my #1 film from director F.W. Murnau:

1) Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927)

2) Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens {Nosferatu} (1922)

3) Faust - Eine deutsche Volkssage {Faust} (1926)

4) Der Letzte Mann {The Last Laugh} (1924)

5) Herr Tartüff {Tartuffe} (1926)

Currently my #8 silent film:

1) Modern Times (1936, Charles Chaplin)

2) Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari. {The Cabinet Of Dr. Caligari} (1920, Robert Wiene)

3) Metropolis (1927, Fritz Lang)

4) Frau im Mond {Woman in the Moon} (1929, Fritz Lang)

5) Körkarlen {The Phantom Chariot} (1921, Victor Sjöström)

6) City Lights (1931, Charles Chaplin)

7) Sherlock Jr. (1924, Buster Keaton)

8) Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927, F.W. Murnau)

9) Bronenosets Potyomkin {The Battleship Potemkin} (1925, Sergei M. Eisenstein)

10) Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens {Nosferatu} (1922, F.W. Murnau)

1st Academy Awards, 1929:

* Best Picture, Unique and Artistic Production (win)

* Best Cinematography - Charles Rosher, Karl Struss (win)

* Best Actress in a Leading Role - Janet Gaynor (also for Seventh Heaven (1927) and Street Angel (1928)) (win)

* Best Art Direction - Rochus Gliese (nomination)

National Film Preservation Board, USA:

* Selected for National Film Registry, 1989 Extracts from reviews of other Murnau pictures:

Extracts from reviews of other Murnau pictures:

"To fans of early horror, director F.W. Murnau is best known for Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens, his chilling 1922 vampire film, inspired by Bram Stoker's famous novel. However, his equally impressive Faust (1926) is often overlooked, despite some remarkable visuals, solid acting, a truly sinister villain, and an epic tale of love, loss and evil... Relying very heavily on visuals, 'Faust' contains some truly stunning on screen imagery, most memorably the inspired shot of Mephisto towering ominously over a town, preparing to sow the seeds of the Black Death. A combination of clever optical trickery and vibrant costumes and sets makes the film an absolute delight to watch, with Murnau employing every known element – fire, wind, smoke, lightning – to help produce the film's dark tone. Double exposure is used extremely effectively, being an integral component in many of the visual effects shots."

"Frequent collaborator Emil Jannings is undoubtedly the star of The Last Laugh (1924), occupying almost the entire screen time, and playing the character about whom the story revolves. Performing with a passion that transcends the technical boundaries of the silent film, Jannings gives a truly heart-breaking performance that is worth the price of admission alone... I found myself likening the style to that of the Italin neo-realism movement, if only for showing an average, not-particularly-important man overwhelmed by the cruelty of upper-class society. However, several scenes diverge from this mould, most specifically a dizzying, wondrous dream sequence, and a tacked-on optimistic ending imposed by the commercially-insecure studio. Though it was not the first film to exploit a moving camera, I've rarely seen a silent film making better use of the technique."

"Herr Tartüff / Tartuffe (1925) was apparently forced upon Murnau by contractual obligations with Universum Film (UFA), and you suspect that perhaps his heart wasn't quite in it, but the end result nonetheless remains essential viewing, as are all the director's films... The tale of Tartuffe himself is worth watching for its technical accomplishments, even if the story itself seems somewhat generic and uninteresting. Most astounding is Murnau's exceptional use of lighting {assisted, of course, by cinematographer Karl Freund}, and, in many cases, entire rooms are seemingly being illuminated only by candlelight... Jannings predictably gives the finest performance, playing the unsavoury title character with a mixture of sly arrogance and lustful repugnance; nevertheless, the role falls far short of the silent actor's greatest performances..."

Wednesday, February 6, 2008

Target #184: The Pilgrim (1923, Charles Chaplin)

TSPDT placing: #753

Directed by: Charles Chaplin (uncredited)

Written by: Charles Chaplin

Starring: Charles Chaplin, Edna Purviance, Kitty Bradbury, Syd Chaplin, Mack Swain, Dean Riesner, Charles Reisner

Regardless of the terrific pictures that Charles Chaplin directed in the latter half of his career, he will always be best remembered for his portrayal of the Little Tramp, that bumbling yet kind-hearted vagrant with whom audiences continue to fall in love. Making his debut in Kid Auto Races at Venice (1914), Chaplin's "Little Fellow" soon became one of cinema's most beloved and recognisable figures, and Chaplin one of Hollywood's biggest stars. Such was the character's success that, prior to 1940, it was a rare occurrence for Chaplin to portray anybody who wasn't the Tramp. One such attempt was in an unfinished short, The Professor (1919), in which Chaplin portrays a poignant, lowly street performer named Professor Bosco. The Pilgrim (1923), at around sixty minutes in length, was the last of Chaplin's "mini-features" before he dedicated his time almost exclusively to feature-length films, and it is interesting in that he doesn't play the Little Tramp, or, if he does, then it's a version of the character that we haven't seen before.

In the film, Chaplin plays an escaped prisoner, who, in his flight from the authorities, is mistaken for the young parson who was supposed to be arriving at a small country town. It wasn't unusual for the Little Tramp to find himself in trouble with the police {and, indeed, he did a spell in prison during Modern Times (1936)}, so it's not altogether unreasonable to conclude that this convict is one and the same character. Despite missing many of his trademarks – the baggy trousers, the cane, the derby hat – his bumbling benevolence is precisely the same, even if one brief flashback shows him sharing a friendly cigarette with an unscrupulous fellow jailbird (Charles Reisner). Notably, a newspaper headline in the film betrays our hero's name to be "Lefty Lombard" alias "Slippery Elm," though these could easily be pseudonyms. 'The Pilgrim' is a film that places more emphasis on plain slapstick than any of Chaplin's feature films, and the pathos that is apparent in most of his works is noticeably lacking, as is any real romantic connection with leading lady Edna Purviance {the final occasion on which the two co-starred}.

Despite the absence of any real emotion, Chaplin's film still succeeds on its own terms, with the criminal's situation allowing for an assortment of amusing scenarios. Dressed as a parson, one is always expected to act in the most civilised fashion, and yet our poor hero finds that he just can't play the part. Chaplin's incredible skill for visual communication is most stunningly apparent in his character's gesticulated re-telling of the David vs Goliath legend, and, without the aid of sound, the audience can easily follow every single detail of the story. Also hilarious are the Pilgrim's attempts at making a cake {using the hat belonging to Chaplin's brother and co-star, Syd}, his response to the antics of Howard Huntington the dishonest thief, and his inability to take a policeman's hint beside the border into Mexico. In 1959, The Pilgrim was one of three films {along with Shoulder Arms (1918) and A Dog's Life (1918)} that Chaplin slightly re-edited and combined to form The Chaplin Revue. He also composed a new soundtrack, as well as a catchy title theme, performed by Matt Monroe, called "I'm Bound for Texas."

7/10

Currently my #3 film of 1923:

1) A Woman of Paris: A Drama of Fate (Charles Chaplin)

2) Safety Last! (Fred C. Newmeyer, Sam Taylor)

3) The Pilgrim (Charles Chaplin)

Tuesday, February 5, 2008

Target #183: The Circus (1928, Charles Chaplin)

TSPDT placing: #455

Directed by: Charles Chaplin

Written by: Charles Chaplin

Starring: Charles Chaplin, Merna Kennedy, Al Ernest Garcia, Harry Crocker

WARNING: Plot and/or ending details may follow!!!

The Circus (1928) was one of the few Charles Chaplin features that I was yet to see, but that wasn't from lack of trying. I first attempted to watch the film mid-way through last year, but, being terribly ill at the time, and having to wake up relatively early the following morning, I barely got half-way through the Tramp's antics before I had to turn off the DVD and go to sleep. For some reason that I can't quite explain, it took until yesterday for me to finally commit to another try, and it was a pleasant and entertaining experience. Though certainly one of Chaplin's lesser efforts, The Circus is an enjoyable and imaginative thread of slapstick gags, with the occasional hint of pathos, though not to the extent of many of the Tramp's other feature-length outings. The circus setting provides an ideal collection of props and scenarios for Chaplin to explore, and many of the film's laughs are derived from his character's hopeless attempts at being a clown, performing magic and tight-rope walking. We first find the Tramp {whom Chaplin liked to call the "little fellow"} at a carnival, completely devoid of money, where a devious pickpocket (Steve Murphy) has stashed his winnings into the Tramp's trouser pocket. As he tries to pickpocket his money back, a policeman catches him, and, completely befuddled, the Tramp finds himself graciously thanking the officer for returning the money that he never knew he had. Needless to say, it doesn't take long before both the Tramp and the pickpocket find themselves frantically fleeing the authorities, and Chaplin takes refuge in a maze of mirrors, where the policemen can certainly see their quarry, but can't decide which of the dozen reflections is real. Following a hot pursuit, the Tramp finds himself scuttling through a circus tent in the middle of a performance, and the audience is left in hysterics by his inadvertently hilarious antics. The The Circus Proprietor (Al Ernest Garcia), desperate for anyone who might save his floundering show, hires the Tramp immediately, but deliberately neglects to inform him that he is the star attraction.

We first find the Tramp {whom Chaplin liked to call the "little fellow"} at a carnival, completely devoid of money, where a devious pickpocket (Steve Murphy) has stashed his winnings into the Tramp's trouser pocket. As he tries to pickpocket his money back, a policeman catches him, and, completely befuddled, the Tramp finds himself graciously thanking the officer for returning the money that he never knew he had. Needless to say, it doesn't take long before both the Tramp and the pickpocket find themselves frantically fleeing the authorities, and Chaplin takes refuge in a maze of mirrors, where the policemen can certainly see their quarry, but can't decide which of the dozen reflections is real. Following a hot pursuit, the Tramp finds himself scuttling through a circus tent in the middle of a performance, and the audience is left in hysterics by his inadvertently hilarious antics. The The Circus Proprietor (Al Ernest Garcia), desperate for anyone who might save his floundering show, hires the Tramp immediately, but deliberately neglects to inform him that he is the star attraction.

As was typical in most of Chaplin's pictures, there is also a love interest that forms the story's emotional heart. Merna Kennedy plays one of the circus performers, the ill-treated step-daughter of the show's proprietor. When they first meet, the Tramp scolds the hungered girl for stealing his meagre breakfast, but quickly takes pity on her, and eventually falls in love. Realising that he lacks the means to provide any respectable life for the women he loves, the Tramp graciously surrenders any notions of marrying her, instead convincing Rex (Harry Crocker), a handsome and upright tight-rope walker, to take her hand in marriage. The film's final image, of Chaplin sitting alone in the newly-deserted field where the circus once resided, is almost achingly poignant, a perfect illustration of the lonely lifestyle that he must lead each day. It was Charles Chaplin, in even his early films, who discovered that tragedy and comedy were never too far apart: though The Circus doesn't quite balance the two as evenly as his various masterpieces, such as Modern Times (1936) and The Great Dictator (1940), it remains a joyous slapstick romp, with more than enough heart to go around.

As was typical in most of Chaplin's pictures, there is also a love interest that forms the story's emotional heart. Merna Kennedy plays one of the circus performers, the ill-treated step-daughter of the show's proprietor. When they first meet, the Tramp scolds the hungered girl for stealing his meagre breakfast, but quickly takes pity on her, and eventually falls in love. Realising that he lacks the means to provide any respectable life for the women he loves, the Tramp graciously surrenders any notions of marrying her, instead convincing Rex (Harry Crocker), a handsome and upright tight-rope walker, to take her hand in marriage. The film's final image, of Chaplin sitting alone in the newly-deserted field where the circus once resided, is almost achingly poignant, a perfect illustration of the lonely lifestyle that he must lead each day. It was Charles Chaplin, in even his early films, who discovered that tragedy and comedy were never too far apart: though The Circus doesn't quite balance the two as evenly as his various masterpieces, such as Modern Times (1936) and The Great Dictator (1940), it remains a joyous slapstick romp, with more than enough heart to go around.1) Steamboat Bill, Jr. (Charles Reisner, Buster Keaton)

2) The Circus (Charles Chaplin)

1) Modern Times (1936)

_01.jpg)

_poster.jpg)