TSPDT placing: #261

Directed by: Charles Chaplin

Written by: Charles Chaplin

Starring: Charles Chaplin, Jackie Coogan, Edna Purviance, Carl Miller, John McKinnon, Charles Reisner

Charles Chaplin was born on April 16, 1889, in East Street, Walworth, London. Though his parents, both music hall entertainers, separated before his third birthday, they also raised him into the entertainment business. His first appearance on film was in Making a Living (1914), a one-reel comedy released on February 2, 1914. It didn't take long for Chaplin to find his niche in the film-making industry, and his character of the Tramp – who first appeared in Kid Auto Races at Venice (1914) – guaranteed his popularity and longevity in the industry. After a string of successful short films, among the most accomplished of which are Shoulder Arms (1918) and A Dog's Life (1918), Chaplin commenced production on his first feature-length outing with the Tramp. The Kid (1921) proved an instant success, becoming the second highest-grossing film of 1921 {behind Rex Ingram's The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921)} and ensuring another fifteen years of comedies featuring Chaplin's most enduring character.

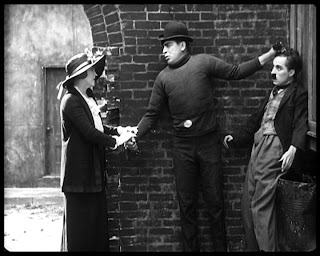

The Kid opens in somewhat sombre circumstances, as a struggling entertainer (Chaplin regular Edna Purviance) emerges from the hospital clasping her unwanted child. Unable, or perhaps unwilling, to care for the infant, she regretfully abandons the baby in an automobile, which is promptly hijacked by unscrupulous criminals. The car thieves discard the orphan in a garbage-strewn alleyway, at which point our humble vagrant hero comes tramping down the street. Upon his discovery of the little bundle-of-joy, Chaplin demonstrates the most practical response, and glances inquiringly upwards, both at the apartment windows through which residents like to toss their leftovers, and at the Heavens, who conceivably might have dropped a newborn from the sky. After several awkward attempts to unload the baby on somebody else, Chaplin lovingly decides to raise the kid himself, crudely fashioning the necessities of child-raising (a milk bottle, a toilet seat) from his own modest possessions. Five years on, the Kid (Jackie Coogan) has blossomed into a devoted and energetic sidekick, a partner-in-crime if you will, and it is then that Chaplin's fatherhood is placed in jeopardy.

The Tramp's young co-star was the son of an actor, and Chaplin first discovered him during a vaudeville performance, when the four-year-old entertained audiences with the "shimmy," a popular dance at the time. Chaplin was delighted with Coogan's natural talent for mimicry, and his ability to precisely impersonate the Tramp's unique expressions and mannerisms – becoming, in effect, a childhood version of Chaplin – was crucial to the film's success. The domestic bond exhibited by the pair is faultless in every regard, and, adding to the poignancy of their relationship, Chaplin began work on the production just days after the death of his own three-day-old newborn son, Norman Spencer Chaplin (during his short-lived marriage to child actor Mildred Harris). The mutual compassion and understanding underlying the central father-son relationship remains very touching nearly ninety years later, particularly when the pair employ their combined talents to promote the continued prolificacy of the Tramp's window-repair business. However, even during proceedings as ordinary as a pancake breakfast, that the two share a genuine affection for one another is beyond question.

According to Chaplin's autobiography, actor Jack Coogan, Sr (who plays several minor roles throughout the film, including the troublesome Devil in the dream sequence) told his young son that, if he couldn't cry convincingly, he'd be sent to a workhouse for real. We can never know for certain if this was the case, but what we do know is that, during the separation sequence, young Coogan delivers one of the most heart-wrenching child performances ever committed to the screen, his hands stretched outwards in a grief-stricken plea for mercy. His performance is intercut with Chaplin grappling frantically with the authorities, his widened eyes staring directly at the camera, as though actively pleading for the audience's sympathy and assistance; it's one of the director's all-time most unforgettable moments, and first decisive instance that Chaplin was able to so seamlessly blend humour and pathos. In the 1970s, Chaplin – ever the perfectionist – re-released the film with a newly-composed score, and deleted three additional sequences involving Purviance as the orphan's mother, which might explain why the kid's father (Carl Miller) apparently serves no use to the story.

8/10

Currently my #2 film of 1921:

1) Körkarlen {The Phantom Chariot} (Victor Sjöström)

2) The Kid (Charles Chaplin)

Currently my #10 film from director Charles Chaplin:

Currently my #10 film from director Charles Chaplin:

1) Modern Times (1936)

2) The Great Dictator (1940)

3) City Lights (1931)

4) Limelight (1952)

5) The Gold Rush (1925)

6) Monsieur Verdoux (1947)

7) A Woman of Paris: A Drama of Fate (1923)

8) Shoulder Arms (1918)

9) A King in New York (1957)

10) The Kid (1921)

Also on the TSPDT top 1000:

#21 - City Lights (1931)

#34 - The Gold Rush (1925)

#52 - Modern Times (1936)

#176 - Monsieur Verdoux (1947)

#252 - The Great Dictator (1940)

#403 - Limelight (1952)

#455 - The Circus (1928)

#753 - The Pilgrim (1923)

#876 - A Woman of Paris (1923)

What others have said:

What others have said:

“Chaplin and Coogan are so in synch here that it's believable that they really are father and son, and others on the set report that Chaplin really did treat the young actor like his son during the prolonged shoot. Like clones from two generations, Chaplin and Coogan successfully bring off virtually perfect comic scenes that come across naturally, but it's the "sentimental" scene that everyone remembers…. The pure anguish that both Coogan and Chaplin display during the separation scene feels so real that we could be watching a documentary paralleling the workhouse days of Dickens' London. Coogan's tears, outstretched arms, and silent wailing all communicate total devastation as do the cuts to Chaplin's underplayed looks of horror and desperation. Combined together, it's a sequence that lives on forever and continually is replayed in Chaplin highlights.”

John Nesbit

“While losing his son undoubtedly reawakened those old boyhood memories, their artistic rendering took place with Charlie's heart, not his head. And the idea probably succeeds because it is largely unconscious rather than self-conscious autobiography…Taking the lowbrow slapstick route, he quarried for bits and shticks, not archetypes and myths. But funny things can happen on that low road to comedy, just as they do on the high road to tragedy. Just as Oedipus and Laius--father and son--encounter each other by chance at one of life's crossroads, so Charlie the fatherless kid and Chaplin the childless father accidentally meet in a London lane. Unlike their ancient predecessors, whose hearts are filled with mistrust and hate, Charlie Chaplin and the lost child are filled with yearning and affection. And so their tale is a bittersweet ballad of love and loss. Griminess is next to Godliness in a comic universe where the disinherited can inherit the earth.”

Stephen M. Weissman

“Unless your heart is as stony as a biblical execution, I challenge you to watch unmoved as Charlie Chaplin's heroic vagabond rescues five-year-old Jackie Coogan from being hauled away to the "orphan asylum." At this point in The Kid, Chaplin's musical score tugs any heartstrings not yet plucked by the look on the Kid's face as he pleads for release, or on the Tramp's as he victoriously embraces the foundling child. Say what you will about Chaplin's deployment of pathos (you can almost see him pulling the pin with his teeth and lobbing it into our laps), this scene in "a picture with a smile and perhaps a tear" is one of those glorious movie moments that demonstrates what the medium can do when the right emotionally haunted, increasingly self-absorbed, control-freak genius is calling the shots.”

Mark Bourne

Extracts of reviews for other Chaplin pictures:

Extracts of reviews for other Chaplin pictures:

"Written, produced and directed by Chaplin, A Woman of Paris is a tightly-paced drama/romance, employing a lot of dialogue (somewhat unusual for Chaplin, who usually relied on extended slapstick comedic set pieces to drive his silent films) and a three-way relationship that has since become commonplace in films of this sort. The film allowed Chaplin to extend his skills beyond the realm of the lovable little Tramp. Unfortunately, this seemingly was not what audiences wanted. Perhaps perceived as a harmful satire of the American way of life, A Woman of Paris was banned in several US states on the grounds of immorality, and it was a commercial flop. Chaplin had conceived the film as a means of launching the individual acting career of Edna Purviance, though this bid was unsuccessful. It did, however, make an international star of Adolphe Menjou."

"Despite the absence of any real emotion in The Pilgrim, Chaplin's film still succeeds on its own terms, with the criminal's situation allowing for an assortment of amusing scenarios. Dressed as a parson, one is always expected to act in the most civilised fashion, and yet our poor hero finds that he just can't play the part. Chaplin's incredible skill for visual communication is most stunningly apparent in his character's gesticulated re-telling of the David vs Goliath legend, and, without the aid of sound, the audience can easily follow every single detail of the story. Also hilarious are the Pilgrim's attempts at making a cake {using the hat belonging to Chaplin's brother and co-star, Syd}, his response to the antics of Howard Huntington the dishonest thief, and his inability to take a policeman's hint beside the border into Mexico."

"A Dog's Life was Chaplin's first film for First National Films, a company founded in 1917 by the merger of 26 of the biggest first-run cinema chains... What is perhaps most impressive about the film is the way in which Chaplin parallels the daily struggles of the Tramp with those of the young dog, Scraps, a Thoroughbred Mongrel... In support of the old adage that good will always be rewarded with good, Chaplin comes to the aid of Scraps when he is being attacked by a gang of predatory dogs, and, in return, the intelligent canine ultimately retrieves the means by which our hero may retire into the country with his sweetheart (Edna Purviance). As in The Pilgrim, the chemistry between Purviance and Chaplin is somewhat unconvincing, but she does elicit a fair amount of empathy in her portrayal of an exploited and cruelly-treated bar singer."

Read More...

Summary only...

When three Soviet diplomats (Sig Ruman, Felix Bressart and Alexander Granach) arrive in Paris to sell off some jewelry confiscated from the Grand Duchess (Ina Claire) during the Bolshevik Revolution, they find it difficult to keep their minds on their work. Far away from the cold, drab apartments of Moscow, the French capital is bustling with life, warmth and prosperity (just forget that the French upper-class are not, in fact, a reasonable yardstick for comparison with the Soviet proletariat). Playful aristocrat Léon (Melvyn Douglas), the Duchess' romantic lover, succeeds in corrupting the bumbling diplomats by flaunting the luxuries of capitalistic society. To ensure that the transaction goes through smoothly, the Soviets send down Ninotchka (Garbo), a curt, tight-lipped Bolshevik with a militant hatred of Capitalism and everything it stands for. Against all odds, the debonair playboy Léon and the belligerent Ninotchka fall for one another, an attraction that ultimately proves more significant than one's national allegiance.

When three Soviet diplomats (Sig Ruman, Felix Bressart and Alexander Granach) arrive in Paris to sell off some jewelry confiscated from the Grand Duchess (Ina Claire) during the Bolshevik Revolution, they find it difficult to keep their minds on their work. Far away from the cold, drab apartments of Moscow, the French capital is bustling with life, warmth and prosperity (just forget that the French upper-class are not, in fact, a reasonable yardstick for comparison with the Soviet proletariat). Playful aristocrat Léon (Melvyn Douglas), the Duchess' romantic lover, succeeds in corrupting the bumbling diplomats by flaunting the luxuries of capitalistic society. To ensure that the transaction goes through smoothly, the Soviets send down Ninotchka (Garbo), a curt, tight-lipped Bolshevik with a militant hatred of Capitalism and everything it stands for. Against all odds, the debonair playboy Léon and the belligerent Ninotchka fall for one another, an attraction that ultimately proves more significant than one's national allegiance. Unfortunately, once love softens the formerly stone-faced Ninotchka, the film shifts from being a lighthearted political farce {not unlike To Be or Not to Be (1942) or Wilder's One, Two, Three (1961)} to a weepy romance. Lubitsch followed Ninotchka with The Shop Around the Corner. What worked so well in the latter film, I thought, was that Lubitsch's heart was not necessarily with the star-crossed lovers – James Stewart and Margaret Sullavan – but with Frank Morgan's shop owner, and his familial relationship with its employees. The three reluctant Soviet diplomats in Ninotchka are utterly charming supporting characters, but too often they are shunned in favour of the central romance, which seems to tread water once, as advertised, Garbo breaks character and enjoys a hearty chuckle. Nevertheless, Melvyn Douglas is magnificently debonair, bringing something distinctly likable to the role of a lazy playboy aristocrat. During her opening act, you can almost see a smile forming beneath Garbo's icy exterior, and she plays the role with just the right amount of breeziness.

Unfortunately, once love softens the formerly stone-faced Ninotchka, the film shifts from being a lighthearted political farce {not unlike To Be or Not to Be (1942) or Wilder's One, Two, Three (1961)} to a weepy romance. Lubitsch followed Ninotchka with The Shop Around the Corner. What worked so well in the latter film, I thought, was that Lubitsch's heart was not necessarily with the star-crossed lovers – James Stewart and Margaret Sullavan – but with Frank Morgan's shop owner, and his familial relationship with its employees. The three reluctant Soviet diplomats in Ninotchka are utterly charming supporting characters, but too often they are shunned in favour of the central romance, which seems to tread water once, as advertised, Garbo breaks character and enjoys a hearty chuckle. Nevertheless, Melvyn Douglas is magnificently debonair, bringing something distinctly likable to the role of a lazy playboy aristocrat. During her opening act, you can almost see a smile forming beneath Garbo's icy exterior, and she plays the role with just the right amount of breeziness. Henri Danglard (Jean Gabin) is a respected theatre producer who lives the high life, despite relying upon financial backers to sustain his extravagant lifestyle. A charming chap, and convincingly debonair given his age, Danglard shares the company of the beautiful but temperamental Lola de Castro (María Félix), into whose bed many have attempted to climb (and probably with little resistance). When Danglard woos a pretty young laundry-worker, Nini (Françoise Arnoul), into dancing the cancan for him, Lola is overrun with jealousy, and all sorts of anarchy takes place amidst this romantic rivalry. Meanwhile, a handsome European prince (Giani Esposito) offers Nini his hand in marriage, but she's not willing to make such a dishonest commitment, more inclined to stay with Danglard, who inevitably plots to discard her as soon as his next promising starlet comes along. Jean Gabin, who had previously worked with Renoir in the 1930s, is terrific in the main role, overcoming his mature age to succeed as a potential lover.

Henri Danglard (Jean Gabin) is a respected theatre producer who lives the high life, despite relying upon financial backers to sustain his extravagant lifestyle. A charming chap, and convincingly debonair given his age, Danglard shares the company of the beautiful but temperamental Lola de Castro (María Félix), into whose bed many have attempted to climb (and probably with little resistance). When Danglard woos a pretty young laundry-worker, Nini (Françoise Arnoul), into dancing the cancan for him, Lola is overrun with jealousy, and all sorts of anarchy takes place amidst this romantic rivalry. Meanwhile, a handsome European prince (Giani Esposito) offers Nini his hand in marriage, but she's not willing to make such a dishonest commitment, more inclined to stay with Danglard, who inevitably plots to discard her as soon as his next promising starlet comes along. Jean Gabin, who had previously worked with Renoir in the 1930s, is terrific in the main role, overcoming his mature age to succeed as a potential lover. It's interesting to compare Hollywood films of the 1950s with their European counterparts. Thanks to the Production Code, most American romantic comedies kept the romance almost entirely platonic, whereas here Renoir's characters speak of sex and adultery as though it is a perfectly acceptable practice. Even the adorable Françoise Arnoul, who occasionally reminded me of Shirley MacLaine, is treated as an openly sexual women, and not just because her character specialises in a dance designed purely to display as much leg as possible. Like many of Renoir's films, the characters themselves aren't clearly defined, and so it's difficult to form an emotional attachment. Indeed, only in the final act does Danglard come clean with the extent to which he romantically exploits his dance recruits, though even this moment is overshadowed by the premiere show of the Moulin Rouge. Perhaps it is through his caricatures that Renoir is making a quip about bourgeois French society – that they're all hiding behind fallacious identities and intentions. Or am I looking too far into this quaint musical comedy?

It's interesting to compare Hollywood films of the 1950s with their European counterparts. Thanks to the Production Code, most American romantic comedies kept the romance almost entirely platonic, whereas here Renoir's characters speak of sex and adultery as though it is a perfectly acceptable practice. Even the adorable Françoise Arnoul, who occasionally reminded me of Shirley MacLaine, is treated as an openly sexual women, and not just because her character specialises in a dance designed purely to display as much leg as possible. Like many of Renoir's films, the characters themselves aren't clearly defined, and so it's difficult to form an emotional attachment. Indeed, only in the final act does Danglard come clean with the extent to which he romantically exploits his dance recruits, though even this moment is overshadowed by the premiere show of the Moulin Rouge. Perhaps it is through his caricatures that Renoir is making a quip about bourgeois French society – that they're all hiding behind fallacious identities and intentions. Or am I looking too far into this quaint musical comedy?

An evening with the Vanderhofs is something akin to a Marx Brothers movie, with each character doing their own thing without regard for what outsiders might think. While some family members test fireworks in the basement, sister Essie (Ann Miller) practices her ballet to the xylophone music of her husband (Samuel S. Hinds), as her uptight Russian instructor Boris (Mischa Auer) complains that everything "stinks." Mother Penny (Spring Byington) attempts to finish writing a play, and Alice (Jean Arthur) slides down the staircase banister. With twelve activities happening at once, it's the farce of Arsenic and Old Lace (1944) without those troublesome murders. But behind all this chaos is the unmistakable unity of a close-knit family, and (as in many Capra films) it only takes a recognisable musical tune to bring together the Vanderhofs – and the snobbish Kirbys – for a collective performance that is genuinely charming in its sincerity. At least you can always be assured that a Frank Capra film will always leave you feeling good about yourself, the world, and the people in it.

An evening with the Vanderhofs is something akin to a Marx Brothers movie, with each character doing their own thing without regard for what outsiders might think. While some family members test fireworks in the basement, sister Essie (Ann Miller) practices her ballet to the xylophone music of her husband (Samuel S. Hinds), as her uptight Russian instructor Boris (Mischa Auer) complains that everything "stinks." Mother Penny (Spring Byington) attempts to finish writing a play, and Alice (Jean Arthur) slides down the staircase banister. With twelve activities happening at once, it's the farce of Arsenic and Old Lace (1944) without those troublesome murders. But behind all this chaos is the unmistakable unity of a close-knit family, and (as in many Capra films) it only takes a recognisable musical tune to bring together the Vanderhofs – and the snobbish Kirbys – for a collective performance that is genuinely charming in its sincerity. At least you can always be assured that a Frank Capra film will always leave you feeling good about yourself, the world, and the people in it. Alongside the compassionate performances of Barrymore and Edward Arnold, enjoyable performances are also given by James Stewart and Jean Arthur, such that they repeated their love affair in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939). You Can't Take It with You was adapted by Capra-regular Robert Riskin from a successful play by George S. Kaufman and Moss Hart. I found it interesting that the screenplay bore what appeared to be a socialist slant, with Martin Vanderhof decidedly rejecting capitalist labour in favour of performing his preferred tasks for a minimum wage. This approach, we are shown, leaves one happier and assists the wellbeing of the entire community. I'm not so certain, however, of Vanderhof's insistence on not paying income tax, on the basis that he's not getting anything back from the government – this doesn't seem socialist, nor does it sound particularly "American," either. Even so, everybody can sympathise with the notion that money isn't everything, and that a single kindhearted gesture can go much further than a thousand dollar bills.

Alongside the compassionate performances of Barrymore and Edward Arnold, enjoyable performances are also given by James Stewart and Jean Arthur, such that they repeated their love affair in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939). You Can't Take It with You was adapted by Capra-regular Robert Riskin from a successful play by George S. Kaufman and Moss Hart. I found it interesting that the screenplay bore what appeared to be a socialist slant, with Martin Vanderhof decidedly rejecting capitalist labour in favour of performing his preferred tasks for a minimum wage. This approach, we are shown, leaves one happier and assists the wellbeing of the entire community. I'm not so certain, however, of Vanderhof's insistence on not paying income tax, on the basis that he's not getting anything back from the government – this doesn't seem socialist, nor does it sound particularly "American," either. Even so, everybody can sympathise with the notion that money isn't everything, and that a single kindhearted gesture can go much further than a thousand dollar bills. Renoir's film undoubtedly feels like an unfinished work, but what exists is nonetheless brilliant. Unlike many unfinished orstudio-butchered would-be masterpieces, that A Day in the Country was not completed to the director's satisfaction causes minimal detriment to the sequences that remain today. The narrative up until the "ending"is perfectly-structured and enjoyable to watch, all planned sequencesup until this point having presumably been filmed without incident. However, after Henri (Georges D'Arnoux) and Henriette (Sylvia Bataille) come together for the first time in a reluctant but passionate embrace, the story then jarringly cuts to a years-later epilogue, a wistful conclusion that reflects on events that seemingly never took place. "Every night I remember," confesses Henriette, as she meets her former one-time lover, having settled on marrying a scruffy imbecile (Paul Temps). But exactly what does she remember? There had been nothing in the film to suggest that she and Henri had fallen in love; this eventuality had always been implied, but never satisfactorily executed.

Renoir's film undoubtedly feels like an unfinished work, but what exists is nonetheless brilliant. Unlike many unfinished orstudio-butchered would-be masterpieces, that A Day in the Country was not completed to the director's satisfaction causes minimal detriment to the sequences that remain today. The narrative up until the "ending"is perfectly-structured and enjoyable to watch, all planned sequencesup until this point having presumably been filmed without incident. However, after Henri (Georges D'Arnoux) and Henriette (Sylvia Bataille) come together for the first time in a reluctant but passionate embrace, the story then jarringly cuts to a years-later epilogue, a wistful conclusion that reflects on events that seemingly never took place. "Every night I remember," confesses Henriette, as she meets her former one-time lover, having settled on marrying a scruffy imbecile (Paul Temps). But exactly what does she remember? There had been nothing in the film to suggest that she and Henri had fallen in love; this eventuality had always been implied, but never satisfactorily executed. A strong cast – including André Gabriello, Jane Marken, Jacques B. Brunius and Renoir himself – bring lighthearted humour to their respective roles, but it is the budding romance (never quite realised) between D'Arnoux and Bataille that form's the story's heart. Following its eventual 1946 release, A Day in the Country was lauded as an "unfinished masterpiece," and I suppose that such a description is appropriate. Had filming been completed, such that the story followed through its intended and logical arc, I can only imagine what a powerful piece of cinema the film might have been. Have you ever had a wonderful dream from which you were woken prematurely? This is how I feel about A Day in the Country. Everything up until the hasty ending is funny, emotional, glorious, and invigorating, yet we're wrenched from the dream-like clasp of Renoir's hand unexpectedly and disappointingly. But I'm an optimist: we should simply be glad that this much of the film exists for us to enjoy. Reflecting on what might have been is a task that should ideally be left to movie characters.

A strong cast – including André Gabriello, Jane Marken, Jacques B. Brunius and Renoir himself – bring lighthearted humour to their respective roles, but it is the budding romance (never quite realised) between D'Arnoux and Bataille that form's the story's heart. Following its eventual 1946 release, A Day in the Country was lauded as an "unfinished masterpiece," and I suppose that such a description is appropriate. Had filming been completed, such that the story followed through its intended and logical arc, I can only imagine what a powerful piece of cinema the film might have been. Have you ever had a wonderful dream from which you were woken prematurely? This is how I feel about A Day in the Country. Everything up until the hasty ending is funny, emotional, glorious, and invigorating, yet we're wrenched from the dream-like clasp of Renoir's hand unexpectedly and disappointingly. But I'm an optimist: we should simply be glad that this much of the film exists for us to enjoy. Reflecting on what might have been is a task that should ideally be left to movie characters. As a result of MGM's influence, A Night at the Opera (1935) bears a remarkable resemblance to an Astaire-Rogers style film (despite most of these being produced at RKO), the only difference being that the bright pair of young performers (here played by Kitty Carlisle and Allan Jones) have the aid of three bumbling comedians to facilitate their happy ending. The tale revolves around young in-love opera singers Rosa and Ricardo, the latter of whom can't achieve the recognition he deserves, due to the overbearing influence of the stuffy virtuoso performer Rodolfo (Walter Woolf King). Groucho, proving that he does have something akin to a heart after all, agrees to help Ricardo achieve success in New York, though he takes a lot of coaxing from Chico and Harpo, who are really just along for the ride. Allan Jones fills in the void that would previously have been played by straight-man Zeppo, though Kitty Carlisle's dazzling opera singer is the highlight of the supporting cast. Also enjoyable is the ever-serious Margaret Dumont and Sig Ruman.

As a result of MGM's influence, A Night at the Opera (1935) bears a remarkable resemblance to an Astaire-Rogers style film (despite most of these being produced at RKO), the only difference being that the bright pair of young performers (here played by Kitty Carlisle and Allan Jones) have the aid of three bumbling comedians to facilitate their happy ending. The tale revolves around young in-love opera singers Rosa and Ricardo, the latter of whom can't achieve the recognition he deserves, due to the overbearing influence of the stuffy virtuoso performer Rodolfo (Walter Woolf King). Groucho, proving that he does have something akin to a heart after all, agrees to help Ricardo achieve success in New York, though he takes a lot of coaxing from Chico and Harpo, who are really just along for the ride. Allan Jones fills in the void that would previously have been played by straight-man Zeppo, though Kitty Carlisle's dazzling opera singer is the highlight of the supporting cast. Also enjoyable is the ever-serious Margaret Dumont and Sig Ruman. I've never really been the greatest fan of the Marx Brothers, but I nonetheless enjoy their witty style of humour – particularly anything that Groucho has to say – and, in this film, I appreciated the greater degree of class afforded by the opera setting. In keeping with MGM's standing as the industry leader in movie musicals, A Night at the Opera even includes several genuine opera performances, and it's the real singing voices of both Carlisle and Jones that you are hearing. Chico and Harpo, likewise, don't miss an opportunity to show off their own impressive musical talents, with the former dancing his fingers across the piano keys, and the latter doing likewise on both a piano and his signature harp. While Duck Soup (1933) may have the greater rate of jokes-per-minute, fans of the Marx Brothers can do much worse than to sit down and enjoy the first of the trio's two most commercial successful films {the other being A Day at the Races (1937)}. Going to the opera has never been this chaotic.

I've never really been the greatest fan of the Marx Brothers, but I nonetheless enjoy their witty style of humour – particularly anything that Groucho has to say – and, in this film, I appreciated the greater degree of class afforded by the opera setting. In keeping with MGM's standing as the industry leader in movie musicals, A Night at the Opera even includes several genuine opera performances, and it's the real singing voices of both Carlisle and Jones that you are hearing. Chico and Harpo, likewise, don't miss an opportunity to show off their own impressive musical talents, with the former dancing his fingers across the piano keys, and the latter doing likewise on both a piano and his signature harp. While Duck Soup (1933) may have the greater rate of jokes-per-minute, fans of the Marx Brothers can do much worse than to sit down and enjoy the first of the trio's two most commercial successful films {the other being A Day at the Races (1937)}. Going to the opera has never been this chaotic. At its surface, one might assume The Shop Around the Corner to simply be the story of two lovers, Klara Novak (Sullavan) and Alfred Kralik (Stewart), who love each other without knowing it. However, Lubitsch's film runs much deeper than that. It's the story of Matuschek and Company, a stylish gift shop in Budapest, and the various human relationships that make the store such a close-knit family. When store-owner Hugo Matuschek (Frank Morgan) begins to suspect his oldest employee of having an affair with his wife, we witness the breakup of two families. There's absolutely no reason why the story should not have been set in the United States – perhaps in the blustery streets of New York – but Lubitsch was deliberately recreating the passions and memories of his former years in Europe, the quaintness of love and life before war brought terror and bloodshed to the doorstep. This subtle subtext brings a more meaningful, personal touch to the film – in fact, even as I write this review, I'm beginning to appreciate the story even more.

At its surface, one might assume The Shop Around the Corner to simply be the story of two lovers, Klara Novak (Sullavan) and Alfred Kralik (Stewart), who love each other without knowing it. However, Lubitsch's film runs much deeper than that. It's the story of Matuschek and Company, a stylish gift shop in Budapest, and the various human relationships that make the store such a close-knit family. When store-owner Hugo Matuschek (Frank Morgan) begins to suspect his oldest employee of having an affair with his wife, we witness the breakup of two families. There's absolutely no reason why the story should not have been set in the United States – perhaps in the blustery streets of New York – but Lubitsch was deliberately recreating the passions and memories of his former years in Europe, the quaintness of love and life before war brought terror and bloodshed to the doorstep. This subtle subtext brings a more meaningful, personal touch to the film – in fact, even as I write this review, I'm beginning to appreciate the story even more. Sullavan and Stewart are both lovely in their respective roles, but I think that it's the supporting cast that really make the film. Each character brings a distinctive personality to the mix, and their interactions are always believable and enjoyable. I especially liked how Lubitsch knowingly directed much of our sympathy towards Hugo Matuschek, who, in any other film, would have been restricted to an underdeveloped, two-dimensional portrayal. Matuschek may have lost the love of his family, but he recaptures it in the affection of his employees, and you experience a heartwarming glow when, in the bitter cold of a Christmas Eve snowstorm, he finds companionship in the freckle-faced young errand-boy (Charles Smith). This genuine warmth towards a supporting character strikes me as being similar to several of Billy Wilder's later creations, for example, Boom Boom Jackson in The Fortune Cookie (1966) or Carlo Carlucci in

Sullavan and Stewart are both lovely in their respective roles, but I think that it's the supporting cast that really make the film. Each character brings a distinctive personality to the mix, and their interactions are always believable and enjoyable. I especially liked how Lubitsch knowingly directed much of our sympathy towards Hugo Matuschek, who, in any other film, would have been restricted to an underdeveloped, two-dimensional portrayal. Matuschek may have lost the love of his family, but he recaptures it in the affection of his employees, and you experience a heartwarming glow when, in the bitter cold of a Christmas Eve snowstorm, he finds companionship in the freckle-faced young errand-boy (Charles Smith). This genuine warmth towards a supporting character strikes me as being similar to several of Billy Wilder's later creations, for example, Boom Boom Jackson in The Fortune Cookie (1966) or Carlo Carlucci in

What others have said:

What others have said: Also recommended from Buster Keaton:

Also recommended from Buster Keaton:

The picture opens with a peaceful street in Warsaw, Poland in 1939, where humble citizens are leisurely going about their business. Suddenly, everybody turns in shock, staring in disbelief at the person who has just sidled up to Mr. Maslowski's delicatessen window – could that possibly be Adolf Hitler? It turns out, however, that he is merely an actor engaged in a local theatre production, where famous performers Joseph and Maria Tura (Jack Benny and Carole Lombard) are staging a Nazi satire. On the eve of opening night, political forces prevent the play from being performed, but those sets and costumes certainly aren't going to go to waste. After Hitler's army marches into Poland without warning, throwing Warsaw into disarray, it falls to these actors to prevent the leakage of top-secret Allied documents to the Gestapo. To avoid execution, Joseph Tura must deliver the acting performance of his career, all the while keeping an eye on his wife, whom he suspects of being unfaithful with a handsome Polish pilot (Robert Stack).

The picture opens with a peaceful street in Warsaw, Poland in 1939, where humble citizens are leisurely going about their business. Suddenly, everybody turns in shock, staring in disbelief at the person who has just sidled up to Mr. Maslowski's delicatessen window – could that possibly be Adolf Hitler? It turns out, however, that he is merely an actor engaged in a local theatre production, where famous performers Joseph and Maria Tura (Jack Benny and Carole Lombard) are staging a Nazi satire. On the eve of opening night, political forces prevent the play from being performed, but those sets and costumes certainly aren't going to go to waste. After Hitler's army marches into Poland without warning, throwing Warsaw into disarray, it falls to these actors to prevent the leakage of top-secret Allied documents to the Gestapo. To avoid execution, Joseph Tura must deliver the acting performance of his career, all the while keeping an eye on his wife, whom he suspects of being unfaithful with a handsome Polish pilot (Robert Stack). The early years of the 1940s provided a unique assortment of Hollywood pictures, with war-time propaganda reaching its manipulative, patriotic climax. Most filmmakers responded to the current political climate with super-serious and often unconvincing drama, but a select few – including Charles Chaplin with The Great Dictator (1940) – decided to unveil the comedic side of war, often layered beneath the tragedy of conflict and persecution. To Be or Not to Be spends a few too many minutes on Robert Stack's comparatively uninteresting Allied spy, but, as soon as Jack Benny re-enters the equation, the farce kicks into full-gear. German-born Sig Ruman is hilarious as the bumbling Col. "Concentration Camp" Ehrhardt, and Billy Wilder obviously thought so highly of the performance that he cast the actor as the very-similar Sgt. Johann Schulz in Stalag 17. We always enjoy seeing our film heroes cleverly out-wit the foolish bad-guys, and when the bad-guys are none other than Adolf Hitler and his band of Nazis, victory is very sweet, indeed.

The early years of the 1940s provided a unique assortment of Hollywood pictures, with war-time propaganda reaching its manipulative, patriotic climax. Most filmmakers responded to the current political climate with super-serious and often unconvincing drama, but a select few – including Charles Chaplin with The Great Dictator (1940) – decided to unveil the comedic side of war, often layered beneath the tragedy of conflict and persecution. To Be or Not to Be spends a few too many minutes on Robert Stack's comparatively uninteresting Allied spy, but, as soon as Jack Benny re-enters the equation, the farce kicks into full-gear. German-born Sig Ruman is hilarious as the bumbling Col. "Concentration Camp" Ehrhardt, and Billy Wilder obviously thought so highly of the performance that he cast the actor as the very-similar Sgt. Johann Schulz in Stalag 17. We always enjoy seeing our film heroes cleverly out-wit the foolish bad-guys, and when the bad-guys are none other than Adolf Hitler and his band of Nazis, victory is very sweet, indeed. 16th Academy Awards, 1943:

16th Academy Awards, 1943:

Jack Lemmon plays Wendell Armbruster, Jr, a wealthy American businessman who boards the first plane to Italy following the news of his father's death. Wendell Armbruster, Sr was killed in an automobile accident while on his annual pilgrimage to the Grand Hotel Excelsior, where he goes, he says, to rejuvenate in their famous Italian mud baths. It doesn't take long, however, for Wendell to discover that his much-respected father had not died alone, and that his secret English mistress of ten years had also perished when their vehicle ploughed off a winding road and into a vineyard. Pamela Piggott (Juliet Mills), the mistress' open-minded daughter, has also arrived in the country to claim her mother's body, and Wendell treats her poorly, his steadfast morals refusing to acknowledge their parents' liaison for the great love that it was. As the two corpses become embroiled in endless lengths of red tape – including the need to acquire two zinc-lined coffins, and no shortage of obscure contracts to be signed – Wendell and Pamela begin to understand their close connection, and form a touching relationship of their own.

Jack Lemmon plays Wendell Armbruster, Jr, a wealthy American businessman who boards the first plane to Italy following the news of his father's death. Wendell Armbruster, Sr was killed in an automobile accident while on his annual pilgrimage to the Grand Hotel Excelsior, where he goes, he says, to rejuvenate in their famous Italian mud baths. It doesn't take long, however, for Wendell to discover that his much-respected father had not died alone, and that his secret English mistress of ten years had also perished when their vehicle ploughed off a winding road and into a vineyard. Pamela Piggott (Juliet Mills), the mistress' open-minded daughter, has also arrived in the country to claim her mother's body, and Wendell treats her poorly, his steadfast morals refusing to acknowledge their parents' liaison for the great love that it was. As the two corpses become embroiled in endless lengths of red tape – including the need to acquire two zinc-lined coffins, and no shortage of obscure contracts to be signed – Wendell and Pamela begin to understand their close connection, and form a touching relationship of their own. Though the two leads both deliver sterling comedic performances, Clive Revill is undoubtedly the film's highlight as Carlo Carlucci, the world's most accommodating hotel manager. Blessed with political connections of all kinds, and an inability to sleep until the hotel's off-season, Carlo darts endlessly across town to tie up all the loose ends, apparently expecting nothing in return – he's probably Wilder's all-time nicest comedic creation. The narrative style is similar to that of Arthur Hiller's The Out of Towners (1970), in that the story is comprised of many consistently-mounting setbacks, though the overall effect is far less frustrating for the audience and spares sufficient time to allow some important character development. There is also a rather unnecessary subplot involving a deported American immigrant and his disturbingly-masculine girlfriend, and the film, however nice its intentions, does run about half an hour overtime. Nevertheless, Avanti! is a mature romantic comedy with memorable performances and a very enjoyable story; I wouldn't be surprised if it warms to me greatly with repeat viewings.

Though the two leads both deliver sterling comedic performances, Clive Revill is undoubtedly the film's highlight as Carlo Carlucci, the world's most accommodating hotel manager. Blessed with political connections of all kinds, and an inability to sleep until the hotel's off-season, Carlo darts endlessly across town to tie up all the loose ends, apparently expecting nothing in return – he's probably Wilder's all-time nicest comedic creation. The narrative style is similar to that of Arthur Hiller's The Out of Towners (1970), in that the story is comprised of many consistently-mounting setbacks, though the overall effect is far less frustrating for the audience and spares sufficient time to allow some important character development. There is also a rather unnecessary subplot involving a deported American immigrant and his disturbingly-masculine girlfriend, and the film, however nice its intentions, does run about half an hour overtime. Nevertheless, Avanti! is a mature romantic comedy with memorable performances and a very enjoyable story; I wouldn't be surprised if it warms to me greatly with repeat viewings. Currently my #15 film from director Billy Wilder:

Currently my #15 film from director Billy Wilder: What others have said:

What others have said:

Currently my #10 film from director Charles Chaplin:

Currently my #10 film from director Charles Chaplin: What others have said:

What others have said: Extracts of reviews for other Chaplin pictures:

Extracts of reviews for other Chaplin pictures:

Peter Sellers is often held to be among cinema's most accomplished comedians, and I can see no reason why this should not be the case. He was an extraordinary chameleon when the role called for it, and no actor ever milked so many laughs from his manipulation of cultural stereotypes, whether that be his fascist German from Dr. Strangelove…, his bumbling Frenchman from The Pink Panther, his vocabulary-challenged Chinese detective from Murder by Death (1976) or his good-natured Indian from this film. Of course, it takes a few moments for you to accept such a well-known actor as playing an Indian, but, by the film's end, it doesn't seem unusual in the slightest. Sellers plays Hrundi V. Bakshi as an affable and friendly outsider, completely out-of-his-depth at such an upper-class get-together. Despite his occasionally tendency to be rather clumsy, he eventually earns the respect of the other party-goers, especially beautiful actress Michele Monet (Claudine Longet), through his kindness and indomitable sense of fun.

Peter Sellers is often held to be among cinema's most accomplished comedians, and I can see no reason why this should not be the case. He was an extraordinary chameleon when the role called for it, and no actor ever milked so many laughs from his manipulation of cultural stereotypes, whether that be his fascist German from Dr. Strangelove…, his bumbling Frenchman from The Pink Panther, his vocabulary-challenged Chinese detective from Murder by Death (1976) or his good-natured Indian from this film. Of course, it takes a few moments for you to accept such a well-known actor as playing an Indian, but, by the film's end, it doesn't seem unusual in the slightest. Sellers plays Hrundi V. Bakshi as an affable and friendly outsider, completely out-of-his-depth at such an upper-class get-together. Despite his occasionally tendency to be rather clumsy, he eventually earns the respect of the other party-goers, especially beautiful actress Michele Monet (Claudine Longet), through his kindness and indomitable sense of fun. The Party was largely improvised from a rudimentary 56-60 page screenplay, and it really does show. There is nothing exceptional about the dialogue, and, though Bakshi gets one or two memorable catch-phrases ("Birdie Num Num!"), the bulk of the humour is purely visual. There was always going to be a risk in extending a single party throughout a 99-minute running-time, and the end result is rather interesting. Between gags, particularly during the dinner sequence, there is a curious sense of vacuousness, and Edwards indulges in an extended period of idleness that no comedy director today would ever be bold enough to leave intact. In one way, this approach is somewhat reassuring; the director is obviously completely comfortable with what he is doing. On the other hand, you wonder if the story is merely stalling itself, in order to consume enough celluloid to make a respectable feature-length. In any case, despite my adverse expectations, The Party turned out to be an adequately funny and even touching comedy, in no small part due to the magnificent talents of its leading man…whatever nationality he might be.

The Party was largely improvised from a rudimentary 56-60 page screenplay, and it really does show. There is nothing exceptional about the dialogue, and, though Bakshi gets one or two memorable catch-phrases ("Birdie Num Num!"), the bulk of the humour is purely visual. There was always going to be a risk in extending a single party throughout a 99-minute running-time, and the end result is rather interesting. Between gags, particularly during the dinner sequence, there is a curious sense of vacuousness, and Edwards indulges in an extended period of idleness that no comedy director today would ever be bold enough to leave intact. In one way, this approach is somewhat reassuring; the director is obviously completely comfortable with what he is doing. On the other hand, you wonder if the story is merely stalling itself, in order to consume enough celluloid to make a respectable feature-length. In any case, despite my adverse expectations, The Party turned out to be an adequately funny and even touching comedy, in no small part due to the magnificent talents of its leading man…whatever nationality he might be.

Aside from Allen and Keaton, numerous smaller roles provide a crucial framework for the overall structure of the film. Tony Roberts is Rob, Singer's old friend and confidant. Paul Simon (of Simon and Garfunkel) plays a record producer who takes a keen interest in both Annie and her singing. Shelley Duvall is a reporter for 'The Rolling Stone' magazine, and a one-time girlfriend of Singer. There are also tiny early roles for Christopher Walken (as Annie's somewhat disturbed brother), Jeff Goldblum (who speaks one memorable line at a party – "Hello? I forgot my mantra") and Sigourney Weaver (who can be briefly glimpsed as Singer's date outside a theatre). Two slightly more unusual cameos come from Truman Capote (as a Truman Capote-lookalike, no less) and scholar Marshall McLuhan (whom Singer suddenly procures from behind a movie poster to declare to a talkative film-goer that "you know nothing of my work!").

Aside from Allen and Keaton, numerous smaller roles provide a crucial framework for the overall structure of the film. Tony Roberts is Rob, Singer's old friend and confidant. Paul Simon (of Simon and Garfunkel) plays a record producer who takes a keen interest in both Annie and her singing. Shelley Duvall is a reporter for 'The Rolling Stone' magazine, and a one-time girlfriend of Singer. There are also tiny early roles for Christopher Walken (as Annie's somewhat disturbed brother), Jeff Goldblum (who speaks one memorable line at a party – "Hello? I forgot my mantra") and Sigourney Weaver (who can be briefly glimpsed as Singer's date outside a theatre). Two slightly more unusual cameos come from Truman Capote (as a Truman Capote-lookalike, no less) and scholar Marshall McLuhan (whom Singer suddenly procures from behind a movie poster to declare to a talkative film-goer that "you know nothing of my work!").

_poster.jpg)