Directed by: Charles Chaplin

Written by: Charles Chaplin

Starring: Charles Chaplin, Jackie Coogan, Edna Purviance, Carl Miller, John McKinnon, Charles Reisner

Charles Chaplin was born on April 16, 1889, in East Street, Walworth, London. Though his parents, both music hall entertainers, separated before his third birthday, they also raised him into the entertainment business. His first appearance on film was in Making a Living (1914), a one-reel comedy released on February 2, 1914. It didn't take long for Chaplin to find his niche in the film-making industry, and his character of the Tramp – who first appeared in Kid Auto Races at Venice (1914) – guaranteed his popularity and longevity in the industry. After a string of successful short films, among the most accomplished of which are Shoulder Arms (1918) and A Dog's Life (1918), Chaplin commenced production on his first feature-length outing with the Tramp. The Kid (1921) proved an instant success, becoming the second highest-grossing film of 1921 {behind Rex Ingram's The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921)} and ensuring another fifteen years of comedies featuring Chaplin's most enduring character.

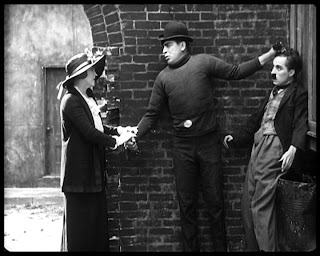

The Kid opens in somewhat sombre circumstances, as a struggling entertainer (Chaplin regular Edna Purviance) emerges from the hospital clasping her unwanted child. Unable, or perhaps unwilling, to care for the infant, she regretfully abandons the baby in an automobile, which is promptly hijacked by unscrupulous criminals. The car thieves discard the orphan in a garbage-strewn alleyway, at which point our humble vagrant hero comes tramping down the street. Upon his discovery of the little bundle-of-joy, Chaplin demonstrates the most practical response, and glances inquiringly upwards, both at the apartment windows through which residents like to toss their leftovers, and at the Heavens, who conceivably might have dropped a newborn from the sky. After several awkward attempts to unload the baby on somebody else, Chaplin lovingly decides to raise the kid himself, crudely fashioning the necessities of child-raising (a milk bottle, a toilet seat) from his own modest possessions. Five years on, the Kid (Jackie Coogan) has blossomed into a devoted and energetic sidekick, a partner-in-crime if you will, and it is then that Chaplin's fatherhood is placed in jeopardy.

The Tramp's young co-star was the son of an actor, and Chaplin first discovered him during a vaudeville performance, when the four-year-old entertained audiences with the "shimmy," a popular dance at the time. Chaplin was delighted with Coogan's natural talent for mimicry, and his ability to precisely impersonate the Tramp's unique expressions and mannerisms – becoming, in effect, a childhood version of Chaplin – was crucial to the film's success. The domestic bond exhibited by the pair is faultless in every regard, and, adding to the poignancy of their relationship, Chaplin began work on the production just days after the death of his own three-day-old newborn son, Norman Spencer Chaplin (during his short-lived marriage to child actor Mildred Harris). The mutual compassion and understanding underlying the central father-son relationship remains very touching nearly ninety years later, particularly when the pair employ their combined talents to promote the continued prolificacy of the Tramp's window-repair business. However, even during proceedings as ordinary as a pancake breakfast, that the two share a genuine affection for one another is beyond question.

According to Chaplin's autobiography, actor Jack Coogan, Sr (who plays several minor roles throughout the film, including the troublesome Devil in the dream sequence) told his young son that, if he couldn't cry convincingly, he'd be sent to a workhouse for real. We can never know for certain if this was the case, but what we do know is that, during the separation sequence, young Coogan delivers one of the most heart-wrenching child performances ever committed to the screen, his hands stretched outwards in a grief-stricken plea for mercy. His performance is intercut with Chaplin grappling frantically with the authorities, his widened eyes staring directly at the camera, as though actively pleading for the audience's sympathy and assistance; it's one of the director's all-time most unforgettable moments, and first decisive instance that Chaplin was able to so seamlessly blend humour and pathos. In the 1970s, Chaplin – ever the perfectionist – re-released the film with a newly-composed score, and deleted three additional sequences involving Purviance as the orphan's mother, which might explain why the kid's father (Carl Miller) apparently serves no use to the story.

8/10

Currently my #2 film of 1921:

1) Körkarlen {The Phantom Chariot} (Victor Sjöström)

2) The Kid (Charles Chaplin)

Currently my #10 film from director Charles Chaplin:

Currently my #10 film from director Charles Chaplin:1) Modern Times (1936)

2) The Great Dictator (1940)

3) City Lights (1931)

4) Limelight (1952)

5) The Gold Rush (1925)

6) Monsieur Verdoux (1947)

7) A Woman of Paris: A Drama of Fate (1923)

8) Shoulder Arms (1918)

9) A King in New York (1957)

10) The Kid (1921)

Also on the TSPDT top 1000:

#21 - City Lights (1931)

#34 - The Gold Rush (1925)

#52 - Modern Times (1936)

#176 - Monsieur Verdoux (1947)

#252 - The Great Dictator (1940)

#403 - Limelight (1952)

#455 - The Circus (1928)

#753 - The Pilgrim (1923)

#876 - A Woman of Paris (1923)

What others have said:

What others have said:“Chaplin and Coogan are so in synch here that it's believable that they really are father and son, and others on the set report that Chaplin really did treat the young actor like his son during the prolonged shoot. Like clones from two generations, Chaplin and Coogan successfully bring off virtually perfect comic scenes that come across naturally, but it's the "sentimental" scene that everyone remembers…. The pure anguish that both Coogan and Chaplin display during the separation scene feels so real that we could be watching a documentary paralleling the workhouse days of Dickens' London. Coogan's tears, outstretched arms, and silent wailing all communicate total devastation as do the cuts to Chaplin's underplayed looks of horror and desperation. Combined together, it's a sequence that lives on forever and continually is replayed in Chaplin highlights.”

John Nesbit

“While losing his son undoubtedly reawakened those old boyhood memories, their artistic rendering took place with Charlie's heart, not his head. And the idea probably succeeds because it is largely unconscious rather than self-conscious autobiography…Taking the lowbrow slapstick route, he quarried for bits and shticks, not archetypes and myths. But funny things can happen on that low road to comedy, just as they do on the high road to tragedy. Just as Oedipus and Laius--father and son--encounter each other by chance at one of life's crossroads, so Charlie the fatherless kid and Chaplin the childless father accidentally meet in a London lane. Unlike their ancient predecessors, whose hearts are filled with mistrust and hate, Charlie Chaplin and the lost child are filled with yearning and affection. And so their tale is a bittersweet ballad of love and loss. Griminess is next to Godliness in a comic universe where the disinherited can inherit the earth.”

Stephen M. Weissman

“Unless your heart is as stony as a biblical execution, I challenge you to watch unmoved as Charlie Chaplin's heroic vagabond rescues five-year-old Jackie Coogan from being hauled away to the "orphan asylum." At this point in The Kid, Chaplin's musical score tugs any heartstrings not yet plucked by the look on the Kid's face as he pleads for release, or on the Tramp's as he victoriously embraces the foundling child. Say what you will about Chaplin's deployment of pathos (you can almost see him pulling the pin with his teeth and lobbing it into our laps), this scene in "a picture with a smile and perhaps a tear" is one of those glorious movie moments that demonstrates what the medium can do when the right emotionally haunted, increasingly self-absorbed, control-freak genius is calling the shots.”

Mark Bourne

Extracts of reviews for other Chaplin pictures:

Extracts of reviews for other Chaplin pictures:"Written, produced and directed by Chaplin, A Woman of Paris is a tightly-paced drama/romance, employing a lot of dialogue (somewhat unusual for Chaplin, who usually relied on extended slapstick comedic set pieces to drive his silent films) and a three-way relationship that has since become commonplace in films of this sort. The film allowed Chaplin to extend his skills beyond the realm of the lovable little Tramp. Unfortunately, this seemingly was not what audiences wanted. Perhaps perceived as a harmful satire of the American way of life, A Woman of Paris was banned in several US states on the grounds of immorality, and it was a commercial flop. Chaplin had conceived the film as a means of launching the individual acting career of Edna Purviance, though this bid was unsuccessful. It did, however, make an international star of Adolphe Menjou."

"Despite the absence of any real emotion in The Pilgrim, Chaplin's film still succeeds on its own terms, with the criminal's situation allowing for an assortment of amusing scenarios. Dressed as a parson, one is always expected to act in the most civilised fashion, and yet our poor hero finds that he just can't play the part. Chaplin's incredible skill for visual communication is most stunningly apparent in his character's gesticulated re-telling of the David vs Goliath legend, and, without the aid of sound, the audience can easily follow every single detail of the story. Also hilarious are the Pilgrim's attempts at making a cake {using the hat belonging to Chaplin's brother and co-star, Syd}, his response to the antics of Howard Huntington the dishonest thief, and his inability to take a policeman's hint beside the border into Mexico."

"A Dog's Life was Chaplin's first film for First National Films, a company founded in 1917 by the merger of 26 of the biggest first-run cinema chains... What is perhaps most impressive about the film is the way in which Chaplin parallels the daily struggles of the Tramp with those of the young dog, Scraps, a Thoroughbred Mongrel... In support of the old adage that good will always be rewarded with good, Chaplin comes to the aid of Scraps when he is being attacked by a gang of predatory dogs, and, in return, the intelligent canine ultimately retrieves the means by which our hero may retire into the country with his sweetheart (Edna Purviance). As in The Pilgrim, the chemistry between Purviance and Chaplin is somewhat unconvincing, but she does elicit a fair amount of empathy in her portrayal of an exploited and cruelly-treated bar singer."

_poster.jpg)

6 comments:

"Körkarlen" rocks mate, freaking rocks.

Shamefully, I still have not seen "The Kid"...

"Korkarlen" is, indeed, quite awesome. It appears that even Kubrick borrowed a scene from it - the bit where David Holm was beating down the door with an axe was pure Jack Torrance!

I haven't been able to find any of Sjöström's other films, though - I hear that "He Who Gets Slapped (1924)" and "The Wind (1928)" are both great.

Anyway, on to Chaplin. Don't be too shameful about not having seen "The Kid" - I hadn't until the other day. I presume that you're otherwise pretty well-versed in his films?

If you're interested, "The Kid" can be downloaded for free from the Internet Archive:

http://www.archive.org/details/TheKid

I'm not sure about the quality, and you might have to provide your own soundtrack.

Not as well versed as I like, but I know some of his basics ("Modern Times", "The Gold Rush", "The Great Dictator" and "Limelight").

Oh yeah, I couldn't stop thinkking about Torrance on that scene from "Korkarlen"!

If you haven't seen it yet, I reckon you'd really like "Monsieur Verdoux (1947)."

You don't usually associate Chaplin with black comedy, but the humour is every bit as sharp as "Kind Hearts and Coronets (1949)" or "The Ladykillers (1955)."

Eh, I can't say this is one of my favorite Chaplins. I find it lacking in both the humor and pathos that City Lights and Modern Times do so well in. Oh well.

Really want to see Korkarlen, by the way.

Post a Comment